About the event

Watch the video recording of this event here:

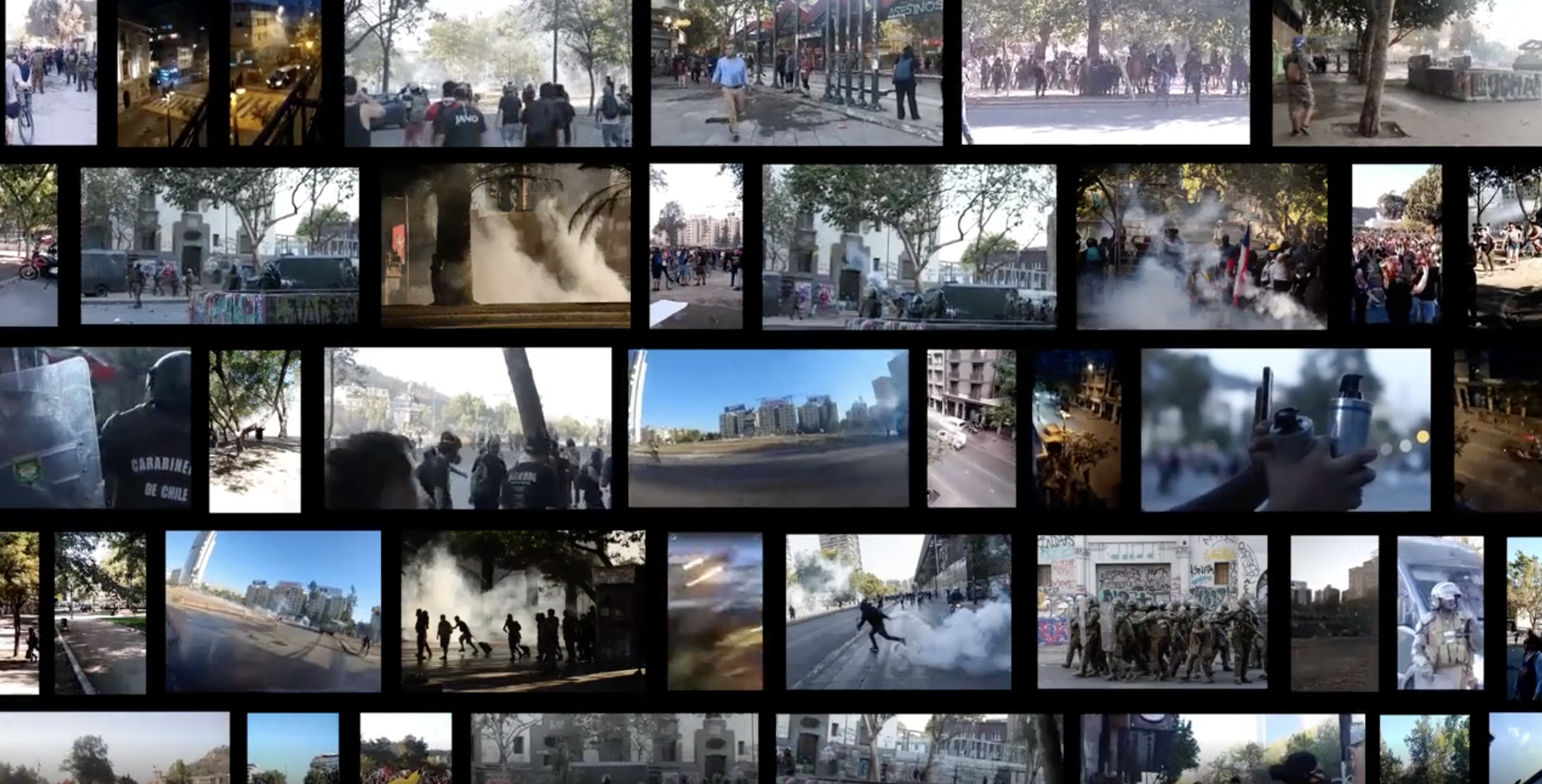

"The defiant protester. The running crowd. The chaos. You may have seen so many shots of tear gas smoke that these images have come to feel like stock photography. A poison cloud that has become a lazy signifier of troubled times, a metaphor that has lost its power through repetition. You turn the page. You flick the channel. Your thumb scrolls down the Tweeter feed. After all, they say it’s safe.”

These are the introductory lines of Anna Fiegenbaum’s Tear Gas: From the Battlefields of WWI to the Streets of Today (Verso 2017). As Fiegenbaum suggests, the image of this “poison cloud” has become repetitive, so much so that it seems it has lost its power. Moreover, because tear gas has been historically (and conveniently) categorized as a “non-lethal” weapon, countries around the globe, including most democratic regimes, continue to buy this highly toxic weapon from manufacturers based in the US, Brazil, and Israel, among other countries, and authorize its deployment against civilians as a method of crowd control.

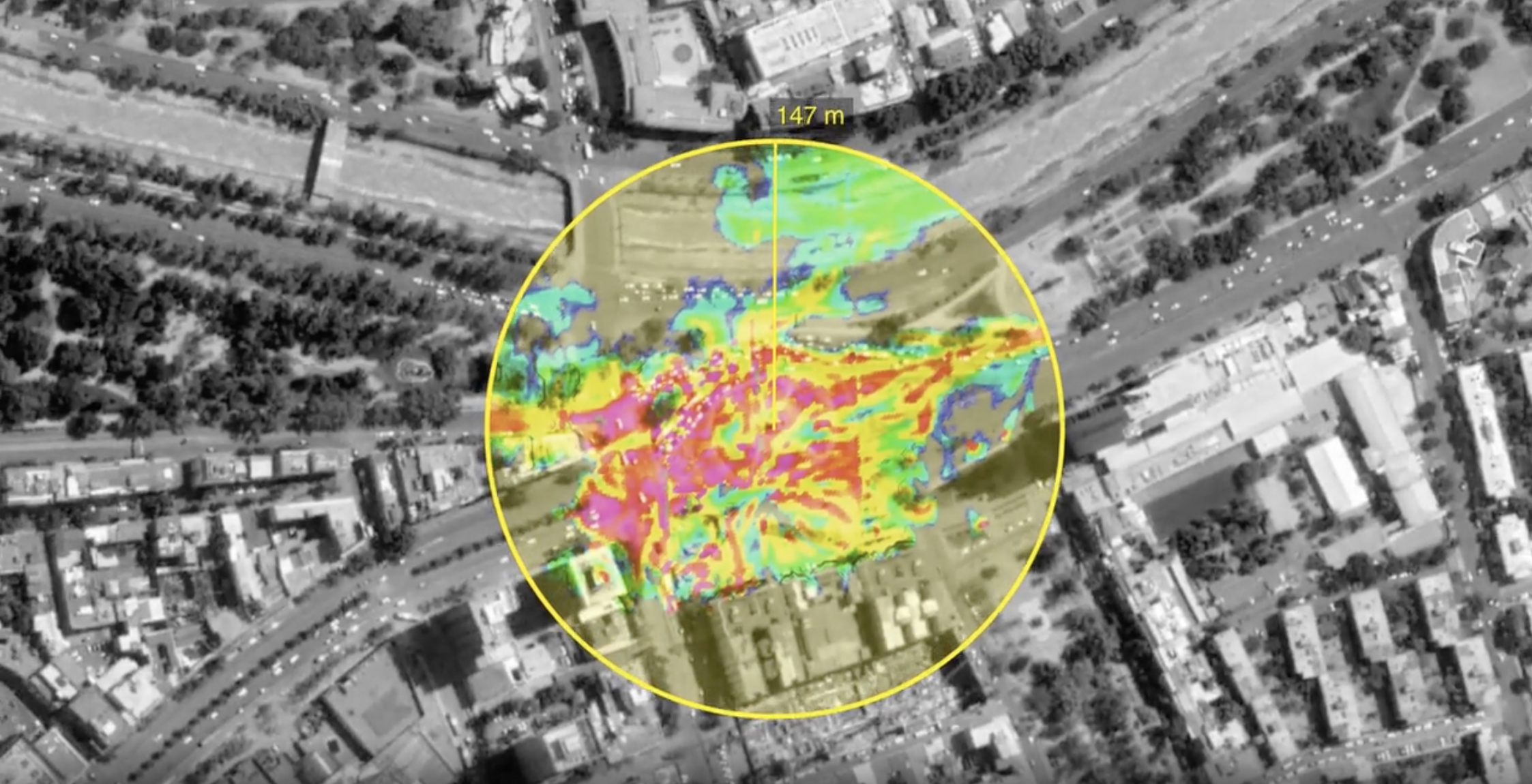

Protesters know, because they have experienced its effects on their bodies, that tear gas is toxic. However, as it happens with other toxic clouds, it is difficult to establish a causality between tear gas and varied health conditions, and it is even harder to provide visual evidence of the lasting presence of chemical toxics in the environment after the toxic cloud “disappears”—written here between quotation marks, because the toxicity of the cloud doesn’t go away, really.

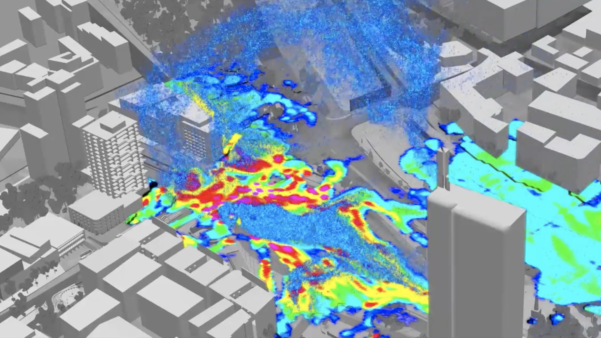

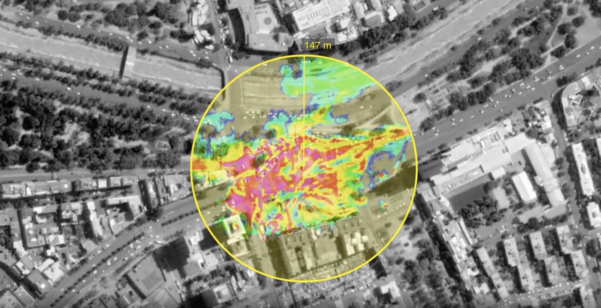

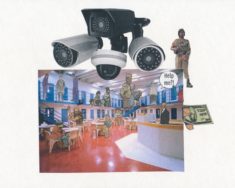

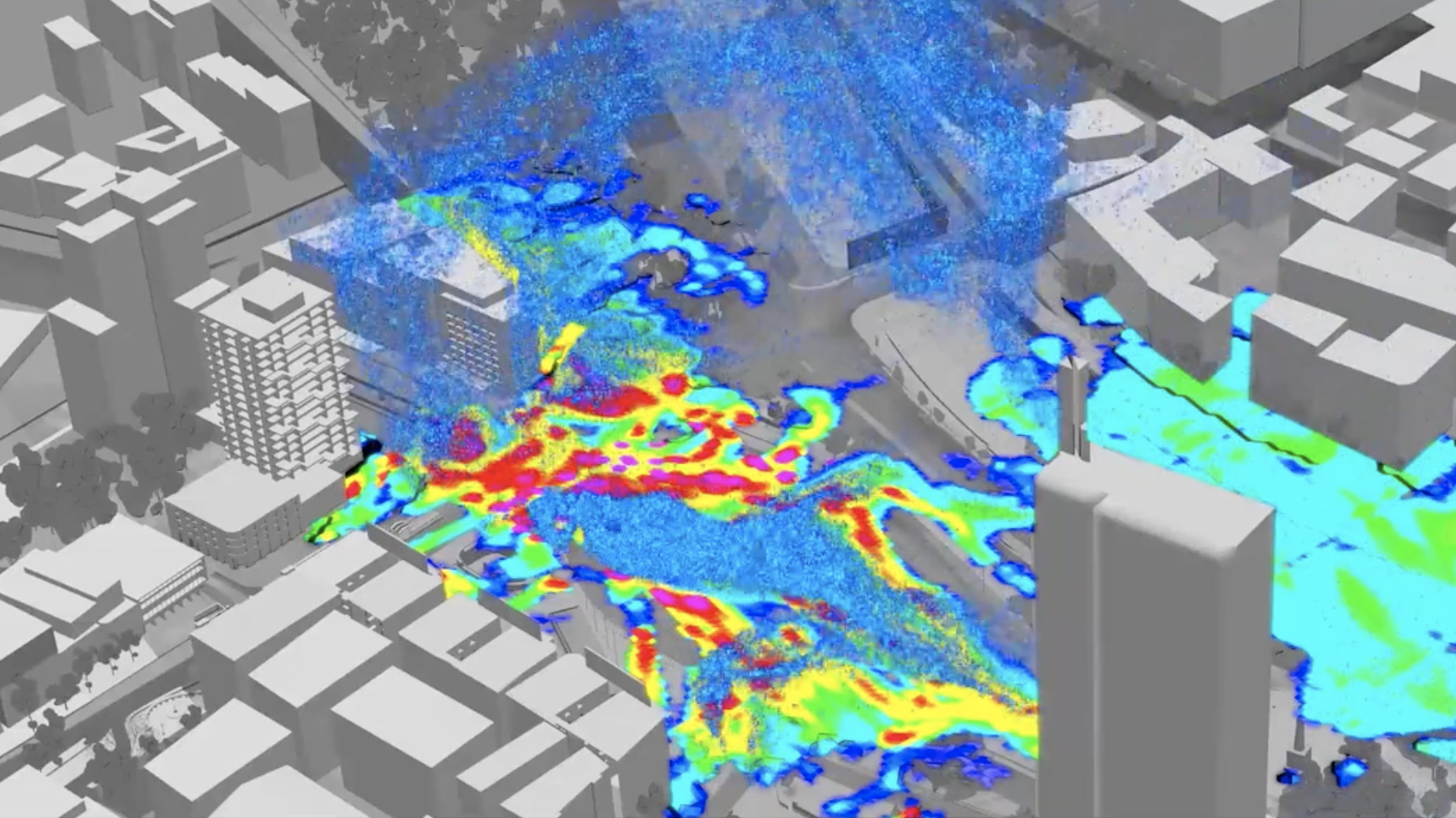

Over the past few years, Forensic Architecture, a research agency based at Goldsmiths, University of London that investigates human rights violations, has developed different tools and methodologies to study, visualize, and socialize toxic clouds, partnering along the way with scientists, mathematicians, and activists.

What are toxic clouds? How do they behave? What methodologies have been developed to study and visualize them? And also, why should we, the public, care about them? Similarly, if tear gas is toxic and lethal, then why do governments continue to authorize its use against civilians in their own countries?

Join us for a conversation with Dr. Samaneh Moafi, Senior Researcher at Forensic Architecture, Imani Jacqueline Brown, artist, activist, and researcher at Forensic Architecture, Robert Trafford, Research Coordinator at Forensic Architecture, and Dr. Anna Fiegenbaum, author of Tear Gas: From the Battlefields of WWI to the Streets of Today (Verso 2017) and Associate Professor in Communication and Digital Media at Bournemouth University, England. The panel will be moderated by Dr. Ángeles Donoso Macaya, Faculty Seminar Lead of the Archives in Common project.

Click here to Register for this event and for access to the Zoom link.

Read Ángeles Donoso Macaya's own words about Archives in Common project and the importance of this event and it's relation to her ongoing work as part of the project:

"The Archives in Common project is underpinned by three key ideas: 1) questions that lead activist research are never formulated in a vacuum or behind closed doors, on the contrary, they emerge from the interactions and exchanges we sustain with activists on the ground; 2) the research that follows is produced in collaboration; and, 3) any research should serve the public good.

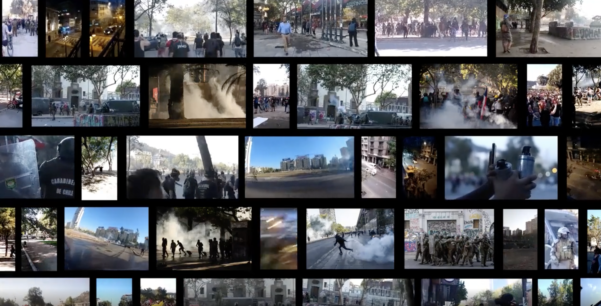

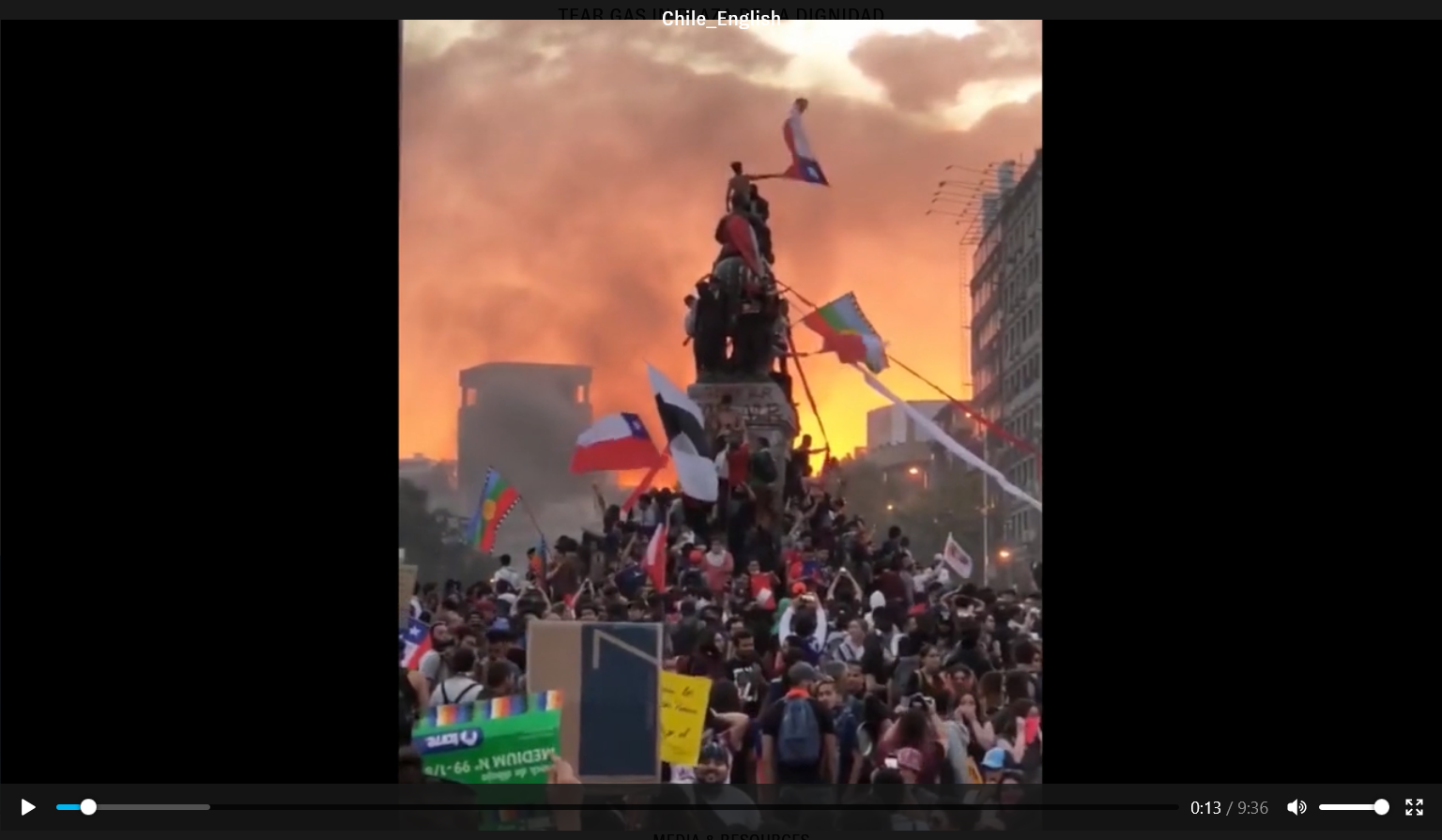

My research centers on documentary theory and history, counter-archival production, and human rights activism. Last year, I collaborated with Forensic Architecture on their investigation about police repression and the use of tear gas in Chile, my home country. In December 2019, while at a protest, I met G. at Plaza de la Dignidad—the epicenter of the uprising that shook the whole country.

We were both hiding in a lateral street, escaping from the tear gas bombs that police agents were firing around the corner. I noticed he was wearing a very sophisticated gas mask—I wasn’t, and my eyes were burning. G. told me he lived in the neighborhood and was part of an activist group, No + Lacrimógenas. He also said that he kept several gas masks at his apartment because some days the air was unbearable, and that he had even installed an AC unit so his daughters could stay at home (it was summer time). We soon realized we were neighbors (I was staying with a friend who lived in the same block unit). That day, G. was outside, doing a tally of the tear gas canisters fired by the police.

After learning more about the work that No + Lacrimógenas was doing on the ground, and the kind of evidence they were trying to gather to legally challenge the use of tear gas in different neighborhoods, I told G. I would try to connect No + Lacrimógenas with Eyal Weizman, founder of Forensic Architecture.

I was familiarized with Forensic Architecture’s work because of my own research. I had already seen several investigations done by them, including Triple Chaser, which also takes on tear gas. Moreover, Thomas Keenan’s and Eyal Weizman’s Mengele’s Skull: The Advent of Forensic Aesthetics (2012) had been a key companion when I was writing my book; it helped me to conceptualize the documentation produced when human remains were found inside an abandoned mine in the town of Lonquén in 1978 as forensic evidence. As I discuss at length in my book The Insubordination of Photography (2020), the investigation that ensued dismantled the dictatorship’s false narrative that the disappeared “didn’t exist.” The few photographs disseminated in independent media and Human Rights publications played a critical role in visualizing and socializing the evidence found inside the mine—they were the evidence presented to the public, to the forum.

Eyal Weizman, connected us with researchers who were already developing studies in Hong Kong, and also with Samaneh Moafi, who soon formed a team to analyze the use of tear gas by the Chilean police. Her team developed a methodology that combined visual open-source investigation and fluid dynamics simulation to analyze and visualize the lasting presence of tear gas droplets in the air, soil, and water. I became one of the collaborators of this investigation, along with my colleague Dr. César Barros A.—together, we researched video footage, contacted local photographers and videographers on the ground, helped to translate news pieces and various documents, and also served as interpreters during interviews with No + Lacrimógenas activists. The product of that investigation is this video"

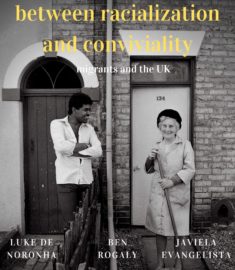

This event is co-sponsored by the Archives in Common: Migrant Practices/Knowledges/Memory project

as part of the Mellon Seminar on Public Engagement and Collaborative

Research from the Center for the Humanities at the Graduate Center CUNY, and by Forensic Architecture, and the Center for Place, Culture and Politics at the Graduate Center, CUNY.