Ángeles Donoso Macaya and Marco Saavedra

In this blog post, we offer a written exchange about the practice of reading together as a form of community building and about our process of building a syllabus that doesn't shy away from big words: ‘creation’, ‘love’, ‘inspiration’, ‘beauty.’ Our syllabus is not centered on specific topics or issues and it does not follow a chronological line. Rather, via poems, quotations, and paintings, it follows the many traces that connect--in different directions--Marco’s own “Constellation of Influences.” We see building a syllabus as a way to share and connect with fellow readers in written form, as an(other) act of love.

Our conversation began with a set of questions that Ángeles posed: What do we understand by, and think about, the process of “working collaboratively,” and the act of knowledge-sharing, of reading together? Why do we think this is a meaningful or important work to do? Also, why and for whom are we building this syllabus?

Ángeles: If Public Humanities is about mobilizing humanistic knowledge, about creating and fostering a sense of community, it is also about democratizing knowledge, about dismantling the intellectual and physical boundaries that separate the knowledge produced within the university and outside of it. As I understand it, this is one of the aims of the syllabus. You, Marco, are sharing your thoughts, views, ideas, about a number of texts and movies, in writing. This virtual “sharing”—I say virtual, because the platform is a website—seeks to mobilize our thinking and even prick us. By “our thinking” I mean us your readers, the readers/students of your syllabus. You are inviting us to read along, to think critically about the texts, movies, and visual art you are sharing with us. This is my take… But maybe you have a different goal in mind, or you see the syllabus differently. How do you see or conceptualize this act of reading collaboratively, collectively? Also, do you think that the format of the syllabus and its platform (the website) are related to, or perhaps can be seen as an effect of, the pandemic context? I ask this because I know that at La Morada you used to have a community library where folks could borrow books; do you see the syllabus as perhaps a continuation, of course in a different form, of this community library? Needless to say, you can propose another route for this short conversation.

Marco: Yes, of course, I think our point of views align politically and morally with the end goal of democratizing knowledge by means of increasing access to agency. To me, it helps to think biblically with the very act of creation being spoken into existence: forming the cosmos out of chaos. What I hope by sharing how I read these texts or works of art in the syllabus form is an interpretation of the cosmos. I am not trying to convince or indoctrinate but rather show: this is where I see beauty and how these beautiful things connect, speak to me, and if they speak to you then we may also form a bridge. That, I think, is the goal of every wild artist—to add to the symphony of creation and hope that others may see it too.

I have always been fascinated with the idea of artists collaborating and being in conversation with one another. I refer to all the artistic icons I look to as my “constellation of influences.” Furthermore, I love for these connections and collaborations to be public, shared, and emulated.

We need to make the artist commune van Gogh never accomplished. We can see the thread in American literature that has Hester Prynne, the protagonist of Nathaniel Hawthorne's 1850 The Scarlet Letter, as one of its founding matriarchs. We can compile lists of takes on whether one is an Artist or a Black Artist from W.E.B. Du Bois (“I stand in utter shamelessness and say that whatever art I have for writing has been used always for propaganda for gaining the right of black folk to love and enjoy.”) to Langston Hughes (“We know we are beautiful. And ugly too.”) to Zora Neale Hurston (“How can any deny themselves the pleasure of my company!”). It is an astounding human legacy and there is no correct way to read it, but I do dare say there are more beautiful ways to arrange it!

Ángeles: Here, you reorient the conversation to the question of love and beauty; you also center the importance of creation, or more precisely, you invite us to think about the act of creation as a collective or communal endeavor. All of this made me think about the accuracy of the term “syllabus”... Yes, we began to talk about this collaboration in terms of a “syllabus.” A syllabus is, by definition, “a summary outline of a discourse, treatise, or course of study or of examination requirements.” But I see no love in this definition, I see no beauty!

I say this because I believe you are offering much more than “a list, a summary or an outline” of key readings. This syllabus—for lack of a better term—is not simply explaining or sharing knowledge “about” certain writers and artists (to be sure, this in and of itself would already be enough); this syllabus is also inciting us to give serious thought to—and to contemplate—the question of love and beauty. Not only are you pouring your heart out, so to speak, in these readings; you are also teaching us to read from and with our hearts.

Can there be liberation without love? Can there be collaboration without love? My answer to both of these questions is: It cannot. Any final thoughts from your part?

Marco: In complete agreement. Whether it be Che Guevara saying “a true revolutionary is guided by a great feeling of love,” or Erich Fromm beginning his book The Art Of Loving by quoting Paracelsus: “He who knows nothing, loves nothing . . . But he who understands also loves, notices, sees [...] The more knowledge is inherent in a thing, the greater the love,” love is the key ingredient in creation, the cornerstone to beauty and the most subversive praxis. Hopefully in outlining these intense loving works of creation our public syllabus can point to learning and liberation.

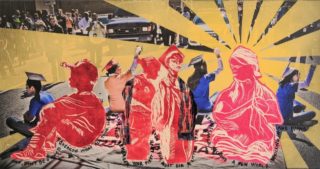

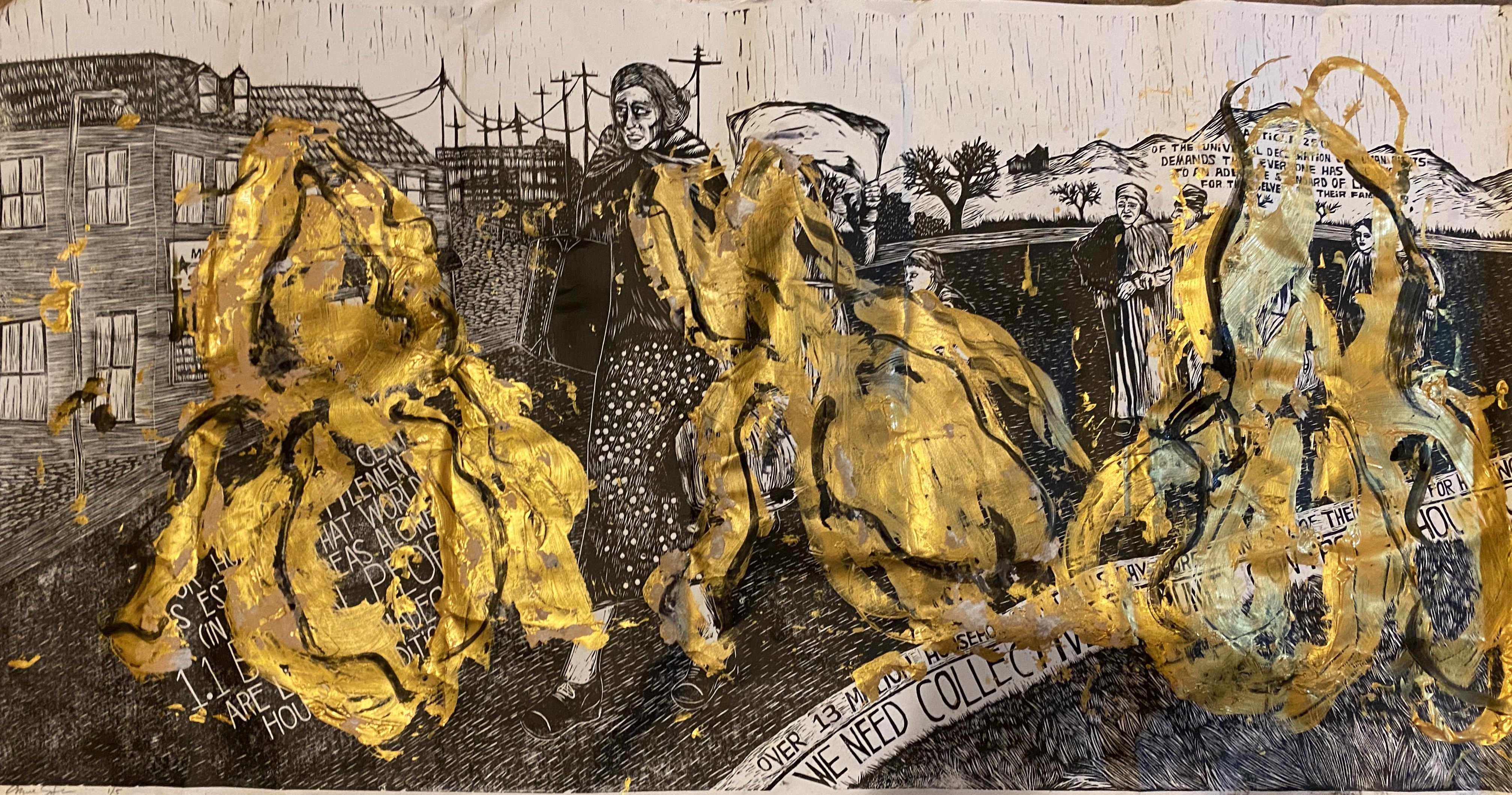

Artist-provided description: “Gilded Irises” is superimposed on Meredith Stern’s “Community Housing” relief print. I completed this mixed-media piece last spring at Maria Sola Park, during the peak of NYC’s first COVID-19 wave. Peak Iris season coincided with record death tolls in NYC, and the juxtaposition couldn’t be more severe. The South Bronx is the poorest congressional district in the city with the highest asthma rate, and the borough is second in infection rate. Our borough suffers from environmental racism and structural poverty that make its citizens more prone to preexisting conditions that compromise our immune systems. During the day my family was committed to feeding our neighbors in need as the best we could do to offer relief, and at night all I could do was seek blessing among irises, like Mary Oliver writes, “they save me, and daily.”

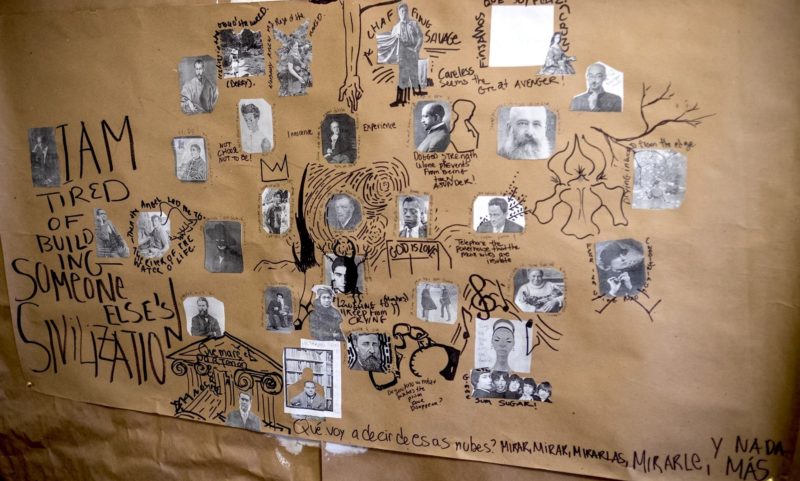

Full description for image 1: A mixed-media collage appears on a piece of what appears to be butcher paper. A cluster of printed-out black-and-white photographs of writers and artists appear surrounded by drawings and writing made in black permanent marker. The following figures appear surrounded by quotations: Fenton Johnson, followed in large text by “I am tired of building someone else’s civilization" and flanked by a photo of Paul Laurence Dunbar; Marc Chagall inside the quote “Then the angel led me to the river of the water o’ life” with angels’ wings drawn on his back; next to a self-portrait by painter Kerry James Marshall titled "The Invisible Man"; next to a photograph of Jean-Michel Basquiat with his signature crown drawn above his head next to a rendering of the tree from Van Gogh’s starry night next to a self-portrait of Vincent Van Gogh; above a photo of a young Franz Kafka with a beetle drawn over half his face; above a painting of Toulouse-Lautrec next to a drawing of a high-heeled leg between a photo of Herman Melville below the words “I prefer not to” and a photo of Zora Neale Hurston next to the words “Laugh to Keep from Crying” (Hughes); above a photo of Henry David Thoreau with an unshackled handcuff coming from his drawing next to the words “Do you know what makes the prison door disappear?”; adjacent to an image of Richard Wright cut out of a picture of a library and pasted back on it, leaving a brown silhouette behind him; next to a drawing of Federico García Lorca inside a drawing of the Parthenon with the words “Quemaré el Partenón para por la noche”; next to the words “Qué voy a decir de esas nubes? Mirar, mirar, mirarlas, mirarle, y nada más.” Above these words, the Rolling Stones appear next to the words “Gimme sum Sugar!” below a drawing of Nina Simone with musical notes drawn around her. Above her are two photos, one of Simon & Garfunkel, the other of Romare Bearden; next to Bearden is a photo of Georgia O’Keefe beneath a drawing of one of her flowers next to a photo of Edna St. Vincent Millay below a drawing of tree branches beneath photos of Junot Diaz and Claude Monet. Above them is a painting of Sor Juana and a space held by Blanka Amezkua; next to a photo of Claude McKay surrounded by the words: “Chaffing savage; careless seems the great avenger” above a photo of W.E.B. DuBois next to a drawing of his silhouette facing the opposite direction above the words “Dogged strength alone prevents from being torn asunder!” above a photo of James Baldwin surrounded by the words “If you don’t know my name you don’t know your own.” Below a drawing of a pulpit reads “God Is Love”; next to a photo of Jean Toomer above the words “telephone the powerhouse that the main wires are insulate” on one side and a painting of William Blake on the other between the two words “Innocence” and “Experience” below a drawing of a long outstretched hand and next to a self-portrait of Egon Schiele next to the Words “Not Choose Not to Be!” and a painting of Gerard Manley Hopkins below a painting of El Greco, a photo of Claudia Muñoz and a photo of Natalia Méndez surrounded by the words: “Nobody knew my rose of the world.”

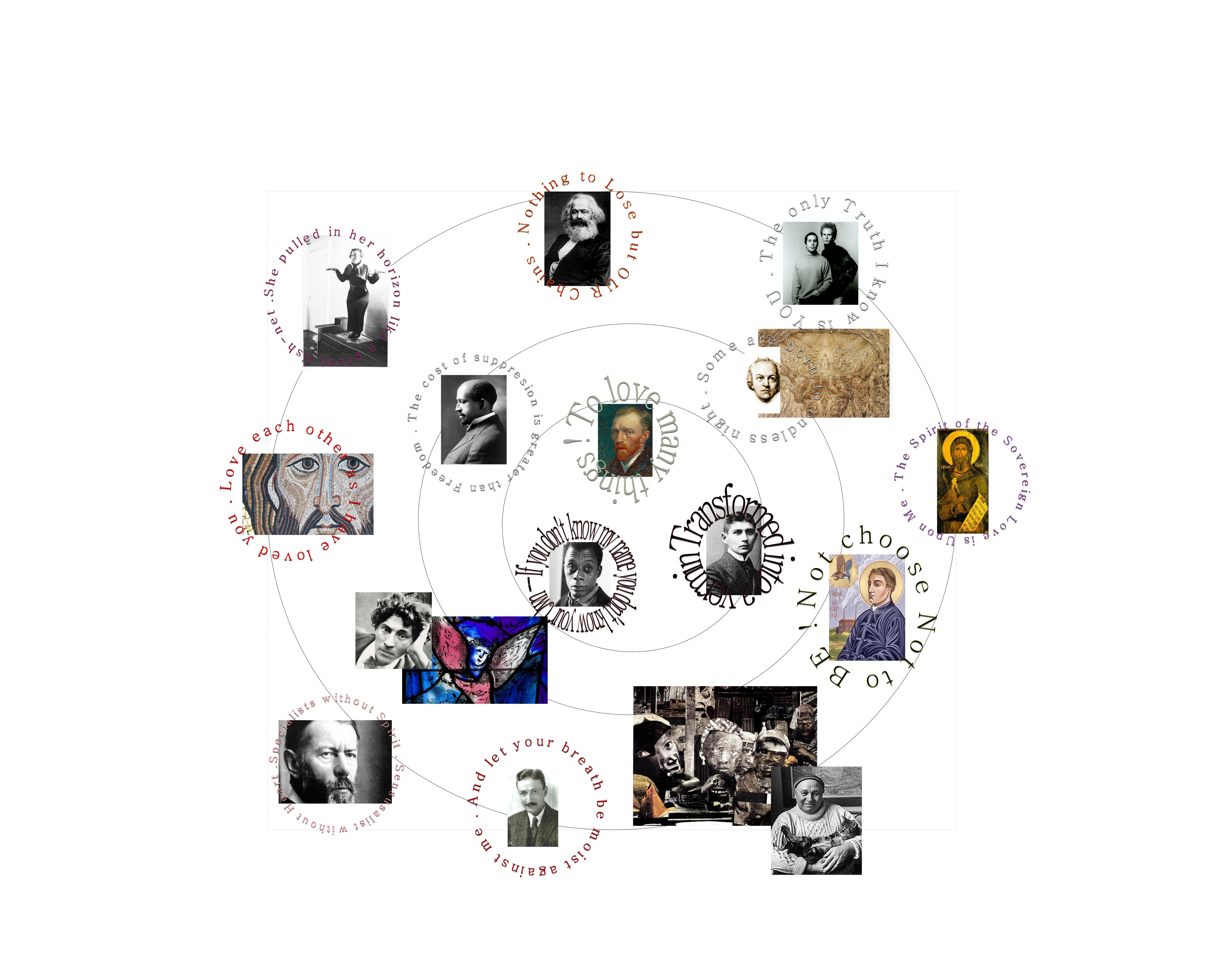

Full description of image 2: A cluster of images appear collaged over a white digital background. The images include black-and-white photographs as well as colorful paintings and portraits of famous writers and historical figures. These images are linked to concentric circles. Around many of the images are circles of text that quote these figures including: James Baldwin, "If you don't know my name you don't know your own;" Gerard Manley Hopkins, "Not choose Not to BE!"; Vincent van Gogh, "To love many things!"; Zora Neale Hurston, "She pulled in her horizon like a fish-net."; W.E.B. DuBois, "The cost of suppression is greater than freedom"; Vincent Van Gogh, "To love many things!"; Jesus, "Love each other as I have loved you."; Max Weber, "Specialists without Spirit. Sensualists without Heart."; Jean Toomer, "And let your breath be moist against me."; a collage by Romare Bearden next to a photo of him; a painting of William Blake, "Some are born to endless night."; Simon & Garfunkel, "The only truth I know is you."; Franz Kafka, "Transformed into vermin"; and Karl Marx, "Nothing to Lose but OUR Chains".