Queenie Sukhadia

The Andrew W. Mellon Seminar on Public Engagement and Collaborative Research is an initiative hosted by the Center for the Humanities that allows creative practitioners, activists and scholars to cohere and work together to undertake research, teaching and other public humanities projects driven by social justice goals.

As I have mentioned in previous essays, I have always been eager to speak with other public humanists (whether or not they explicitly identify as such) about the public humanities in general, and also more specifically about the spectrum of work that is practiced under this rubric. This seminar offered the perfect setting to virtually gather with these practitioners and speak to them about how they understand the work of the public humanities. They share with us, in this interview, their particular understandings of the public humanities, their framings of the publics they are responsible to, what they see the role of a public university being in facilitating this work and how one can reach the ‘public’ through one’s work.

Each week over the next few months, we will be posting a new interview with a member of the Mellon Seminar cohort.

QS: Can you describe your project briefly? Who are your publics? How would you characterize the relationship your project cultivates with these publics? Why did you decide to make your work public-facing?

Ángeles Donoso Macaya: The project “Archives in Common” has various objectives that overlap and respond to key methodological, theoretical, and practical questions. In the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, the main objective—and one that is particularly urgent—is to support the work of initiatives new and old that are led by immigrant organizers and activists in their communities. In this way, our publics include different communities with whom we will work during these next two years (for example, residents of the South Bronx), as well as members of the academic community. In methodological terms, the project seeks to formulate community-centered initiatives in dialogue with community members and activists. Theoretically, the project aims to think collectively about how to build an archive of the commons during a crisis. Both in theory and practice, “Archives in Common” refuses the divisions created by institutions of higher education as colonial and imperial projects—above all, the position of the “expert” and the notion that “He” is authorized to produce and disseminate knowledge about determined “subjects” (the book Decolonizing Ethnography provides a lucid perspective on this critique).

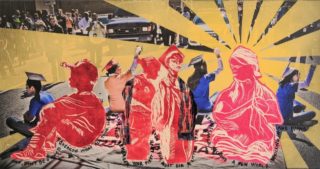

“Archives in Common” is a public-facing project which challenges the operations and the categories and framings deployed by the Archive, understood here as a colonial and imperial operation that produces knowledge about migrants and migrant communities (I am building here on Ariella Azoulay’s Potential History: Unlearning Imperialism).

But what is this “archive in common,” or better yet, what does this “archive in common” do? What our project attempts to do is devise activities (for example, community workshops) which facilitate the sharing of knowledges, experiences, and memories in a way that is non-extractive, where these knowledges, experiences, and memories don’t then become data, information to be analyzed and published. We are devising modes to record, document, and share part of these activities, and also other forms of mutual-aid and community organizing that have emerged during the pandemic. All of this work is being done according to the terms formulated by the activists and community members themselves.

There is a certain kind of pressure placed on immigrant communities to share their stories for different reasons. Yet, categories such as “refugee,” “asylum-seeker,” “illegal,” “alien,” even “undocumented,” already shape and enable particular narratives that then serve to justify particular operations (as an example, in the case of displaced people who are seeking asylum, these operations are not limited to detention and deportation, but also include the requirement that one produces and conforms to a narrative of persecution that meets particular standards and fits certain formats). In this respect, by producing and documenting these narratives, the project also meets another key objective: to contribute to the dissemination of (the lived, ongoing) memory of immigrant communities in New York and to instigate reflections of what the public, the feeling of belonging, and different modes of social visibility mean (I can’t recommend enough Eclipse of Dreams… One of the first events “Archives in Common” co-sponsored last semester was a public talk with the co-authors of this book). Watch the recording of event "The Undocumented-Led Struggle for Freedom: A Conversation with the Authors of Eclipse of Dreams" here:

QS: If you had to select one verb to articulate the work/responsibilities of the public humanities, what would it be?

ÁDM: It is difficult to choose just one verb to describe both work and responsibilities, but I believe that “knowing how to listen” is key. Public Humanities are nourished and made possible by dialogue, participation, and conversations among people within the university and beyond.

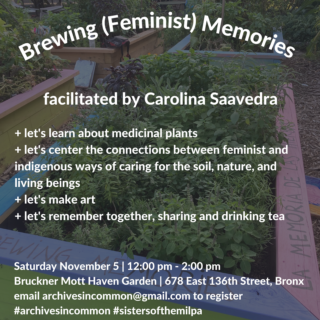

All of this, just like the work of memory, takes time; listening is a process. At the end of our second “Brewing Memories” workshop, Yajaira Saavedra formulated the practice of sharing knowledges, experiences, and memories not only as a testament to the perseverance and presence of indigenous knowledges, but also as a form of mutual aid—another instance of resistance to gentrification that continues to displace and push communities out of the South Bronx. This idea has stayed with me.

QS: What does a 'public university' mean to you? What are its responsibilities?

ÁDM: A public university means, first and foremost, a university that offers free, high-quality education to every person who resides in a territory (be it a city, a state, or a country). In this regard, CUNY falls short of its description. The mission of a public university is to promote the wellbeing of the people and the communities that it serves.

QS: What kinds of institutional supports are needed to facilitate the university’s engagement with the public?

ÁDM: I can speak from my position as a researcher and as a professor. “Archives in Common” is a Public Humanities project. A few weeks ago, I attended an international academic conference—the MLA Convention. This particular forum opened with a conversation about how the humanities can respond to the COVID-19 pandemic. We are living in times of transformation and of crisis: the university also needs to be transformed (there are many groups and coalitions within CUNY and beyond—Free CUNY, the Decolonize CUNY initiative, Rank and File Action, of which I am a member, and other grass-roots groups and organizations—working towards this end). But of course, it is also vital to have the necessary time and financial support to develop and carry out such a transformation. Grants are incredibly valuable; however, it is also important for institutions to reconsider the ways in which they value the different research endeavors and academic achievements of tenure-track faculty. For those working in the humanities, there are limited ways to measure or quantify professional success (peer-reviewed articles, books, academic conference presentations, etc.). Initiatives such as the Mellon Seminar are of tremendous importance, as they allow us to generate and activate forms of producing and disseminating knowledge that do not necessarily conform to the accelerated pace of the neoliberal university—its products or results do not fit into the reductive/exclusive boxes authorized by “academia” and that is actually a good thing!

QS: How do we incentivize publics to engage with the work we do in the university? How do we generate public interest in our work? Is this a worthy goal?

ÁDM: First, you can incentivize your publics by involving them in the different steps of the process. I do not see this project as “my” work. I think it is necessary to interrogate or question the idea of authorship, which is so foundational to scholarly work. In thinking of my participation as a researcher with the project “Archives in Common,” I can say that I identify as an immigrant activist and as a scholar whose research intersects with the study of photography vis-à-vis the work of memory, counter-archival production, and human rights activism. I am also very interested in the documentary mode, in documentary framings and representation. In this sense, the work of promoting initiatives that teach us about the knowledges and traditions of immigrant communities is twofold: to push against narratives that criminalize or victimize immigrants and to help to build and promote the lived, ongoing memory of immigrant communities in New York. This is, or course, a worthy goal.

At the Eclipse of Dreams conversation, Claudia Muñoz, one of the activists who, like, Marco, infiltrated a for-profit detention center in order to advocate release for those inside, said: “My role and duty was to infiltrate, infiltration is the weakening of a system as a whole that I don't believe in and the strengthening of a system I do believe in...” I believe that those of us who are part of the university and who care about its transformation should also act as infiltrators—it is our duty to take as many resources as we can and use them to keep building and sustaining liberatory practices and spaces, where the community can care for itself and continue to flourish, like plants, so that new connections can take root.