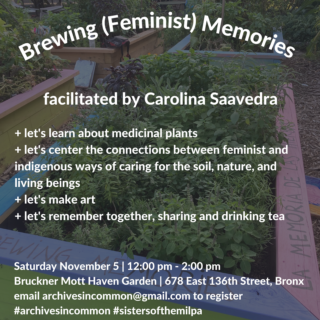

The workshop

“Hello, my name is Carolina Saavedra. I am the daughter of Natalia and Antonio, two farmworkers displaced by NAFTA. I learned traditional indigenous cuisine from my grandmother in Oaxaca; back in the US I studied French cuisine at the International Culinary Arts Center (ICC). Agriculture is ingrained into my DNA.” This is how Carolina Saavedra, chef at La Morada and educator at Stone Barn Center for Food and Agriculture, introduced herself to the participants of the Brewing Memories workshops. From the very start, Carolina drew connections between the practice of agriculture and the experience of forced displacement, the knowledge of traditional indigenous cuisine and of Western culinary arts, her family, memory and cultural identity.

The idea for the Brewing Memories workshops took shape on a trip we took north of NYC to visit the farm, where Carolina works, in early September. I also hoped to help bring back vegetables to her family's restaurant, La Morada, in the city––Carolina regularly transports donations that she collects from other farms north of the city. I also wanted to accompany her because a key part of the Archives in Common project––a project that seeks to support ongoing undocu-immigrant-led work and activism as well as think collectively about how to build an archive of the commons during a crisis––is that initiatives arise from conversation and collaboration; the trip back and forth gave us plenty of time to do precisely that.

On our way up north, Carolina spoke about the educational activities that she had organized at a school near Stone Barn. Thinking of possible workshops, Carolina proposed the idea of organizing one on medicinal plants tailored for the whole family. This is how the idea for the Brewing Memories workshop came about--although the name came later. In this workshop, people would learn about the qualities and medicinal properties of certain plants, use these leaves and stems of these plants to draw a memory, and then consume these memories in the form of tea. The workshop brought the process of learning about plants together with the work of fostering community, in that it emphasized the importance of both learning to take care of ourselves and remembering together, in community. All this pointed to something that I had already mentioned to Carolina––my interest in working with memory and the idea of building a digital archive that is not based on, and which does not reproduce, extractive methodologies, but rather that emerges, and keeps developing further, from the same collaborative process of creating and learning together.

The workshop would also serve to learn about the geographies of each plant––we would learn to distinguish if they were native plants, or if they were brought to the continent as a result of colonization. The selection of plants would depend on what was available at the farmers market each week, not only to support local agriculture, but also to ensure that the plants and herbs we would use had been grown with sustainable practices, without the use of herbicides or pesticides. In both workshops, Carolina explained this organizing principle as part of the methodology.

The garden

On a Friday in early September, I arrived at La Morada around noon to talk briefly with Yajaira Saavedra, an indigenous immigrant activist and co-owner and administrator of La Morada. The idea was to start working on a timeline that would account for the pandemic from the perspective of this restaurant and organizing hub. La Morada is owned and run by the Saavedras, an undocumented family of Mixtec origin who, as a result of their immigration status, have been excluded from all state and federal aid. As we spoke, Yajaira helped to pack the nearly 650 lunches that volunteers would distribute that day. Yajaira designed and has been in charge of coordinating La Morada’s soup kitchen, an immense mutual aid effort that has been operating for over seven months. I had started volunteering with La Morada back in mid-April, when the pandemic was at its peak and La Morada was delivering over 1,200 lunches to families in need every day.

After talking with Yajaira, I met Carolina back at Friends of Brooke Park, a community garden located a couple of blocks from La Morada, where Natalia Mendez (known as “Mamá Morada”), Carolina and many other Mott Haven neighbors grow vegetables and flowers. Carolina wanted to introduce me to Danny, the person in charge of the garden. Our idea was to hold the workshops there. Upon reaching the garden, I was impressed by the space. It was so huge, and there were so many greens! Danny showed us the peppers they were harvesting; I was also mesmerized by the sunflowers. I pictured this garden like a huge lung that was breathing air into Mott Haven. It seemed like the perfect place to do the workshop. It was big enough to ensure that all those who wanted to participate could do so while keeping a safe distance, seated at different tables arranged in a semicircle. There was also a space to make a fire. We told Danny about our plan, and, happily, he said ‘OK.’

Twenty-five people, most of them neighbors of the South Bronx, attended the first workshop held on October 3. On October 24, twenty people attended, many of them for the second time. It was great to see so many familiar faces, because one of our goals was to foster a sense of community, of togetherness. I recall that on October 3, there was a family setting up other tables and chairs to celebrate a birthday party; the day of the second workshop, relatives of the Saavedras were decorating chairs and setting up a huge altar with roses and balloons because they would celebrate a wedding. I found it so meaningful that the garden could be arranged to serve all these different activities—workshops, birthdays, and weddings—for which the community actively used this space.

Brewing memories

The work of memory—i.e., its discussion, its transmission, its preservation—requires time and space. This work, as Marianne Hirsch explains, encompasses various “memory acts”: remembering, imagining, narrating, projecting, documenting, and disseminating (2008). But how do we facilitate the intergenerational transfer of experiences and knowledges and secure the time and space needed for such work in the context of a pandemic? Also, what role can the public university play in such a context? These were the central questions I wanted “Archives in Common” to address, especially because the pandemic has heightened the sense of emergency, as we were dealing with food insecurity, housing insecurity, and job insecurity. There is so much hunger, so much unemployment, and there have been so many deaths. All of this has generated even more anxiety, insecurity, and stress. In thinking through this project, I wanted to ask: how can we take better care of ourselves in this context? And how is this work of care related to the work of memory?

In the workshop series Brewing Memories, the work of memory is performed collectively, where ancestral indigenous practices are oriented towards community care and environmental care. This is essential because it links the work of memory to the environment which makes this work possible. In both workshops, Carolina emphasized the important function of plants as companion species, as pollinizers and pest repellents. These plants are not only beneficial for our bodies and souls (some, like Lavender and Eucalyptus, help us combat stress and anxiety; Spearmint, Mint and Eucalyptus also serve to alleviate cold symptoms; Marigold is good for headaches and is also an anti-inflammatory, as is Lavender), but also for the environment and for the very soil in which they grow.

In addition to teaching us about the medicinal and healing properties of these plants, Carolina also explained and traced the routes of these plants in the context of colonialism (who were the peoples who first discovered the plants, how these plants were, then, transported from one side of the Atlantic to the other). We learned that Marigold was discovered by the Aztecs, while Lavender was discovered by the Romans, and it was later taken over by the French, which is how it reached the Americas. All of this learning integrated the work of memory and all the senses. We learned to recognize plants by how they look, smell, and taste. For example, we had the opportunity to smell, touch and taste two types of Mint: Chocolate Mint and Pineapple Mint. All of us were given two different leaves. Carolina asked us to smell and try them separately and to say whether they tasted like chocolate or pineapple. Most of us got it right!

On October 24, Carolina began by asking participants to choose three words out of a list we had prepared previously, and write up feelings, ideas or memories related to these words. Then, participants used the words they had written to sketch a drawing on a piece of paper, and then used the sketch to draw a memory over a piece of cheese cloth. On both occasions, participants drew their memory using honey and pieces of dried plants. A few participants shared their drawings and the memories these drawings represented. Afterwards, participants tied the cloth together, forming a tea bag that contained their memory, and we all drank and shared tea together.

An archive in common

I understood the Brewing Memories workshops as a way to put into practice—and movement—the idea of an archive in common under the constraints of COVID-19. I had spent time reading and thinking about the archive, which I have come to understand as more than a series of documents, but also a place, a practice, and a series of operations. Scholarship on archives has shown us (or better yet, has opened up to critique) the inextricable relation between the archive and the state, and between the operating mechanisms of the archive and state machineries. These studies reveal the imperial dimension of the archive as something that defines and catalogues subjects while silencing their voices and erasing their experiences. It produces knowledge through extracting information—using concepts and categories designed by others, by the “experts.” The archive as an imperial object discriminates and prohibits access to this knowledge. However, as Ariella Azoulay (2019) argues, there is not one single definition or mode of being of the archive and in the archive; on the contrary, there exists an array of modes in which people interact with the archive and its operations. [1]

What should an archive in common register? What documents should it gather, and for what purpose? Similarly, what are the uses of this archive? I asked myself these questions, although I know that there are other ways of making archives--counter-archival practices, non-imperial and non-extractive ways of creating, documenting, and sharing information and knowledge.

For example, in the context of the Chilean civic-military dictatorship, a topic which I’ve written about elsewhere, a vital counter-archive began to materialize very early on––i.e., within months after the September 11, 1973, coup--assuming an array of forms: it became manifest in the acts of registering, accounting for, and denouncing Human Rights violations, such as torture and forced disappearance. These archival practices were devised and carried out by different groups and were also disseminated publicly: relatives and loved ones pinned the portraits of disappeared victims and took to the streets. Carrying publicly the portraits of those who the military and state agents had disappeared, relatives not only demanded justice on behalf of their loved ones, but also made their (denied) existence visible, present. They also demanded of us, fellow citizens, not to forget about these crimes and about the victims. By refusing to accept the lies perpetrated by the military state, including the notion that ongoing, actual crimes were something “of the past”––or even worse, that they hadn’t happened––the different archival practices, forms, and operations devised by civilians and different groups resisted what Azoulay calls the “imperial” modality of the archive. The documents and objects these counter-archival practices produced (countless photographic portraits, written reports, books, documentary films, and so on) were not, to use Azoulay’s words, “items of a completed past, but, rather the active elements of a common present.” [2]

I evoke this seemingly unrelated case because the answer to the questions stated above are always contingent. In this case, the answer lies in the forms and operations that an archive in common takes during the context of a pandemic. Many of the practices that emerge under conditions of emergency and crisis are often lost afterwards, or are never even registered. Nonetheless, there is a lasting memory of the many forms of resistance and survival that take shape in moments of need. If the archive is an operation––if it’s more than the sum of documents contained within––then what forms might an archive in common take under the COVID-19 pandemic? Here, an archive in common cannot be reduced to a single form or function. It must facilitate initiatives that strengthen community connections, and which share knowledges and practices through popular education. An archive in common seeks to document and register these initiatives in order to expand and to circulate memory of the many forms of community-based immigrant activism.

In Brewing Memories, participants not only collectively learn (or remember) indigenous practices and knowledges centered in the use of medicinal plants as a way to care for oneself, to care for others, and to care for the environment. They also share experiences and memories, and create something from these memories. As Yajaira emphasized in the closing of the second workshop, the practice of sharing knowledges, experiences, and memories around a fire is not only a testament to the perseverance and presence of indigenous knowledges, but also a form of mutual aid—and another instance of resistance to gentrification that continues to displace and push communities out of the South Bronx.

The table

A morada is more than a home, Antonio Saavedra (Natalia’s husband and father to Marco, Carolina and Yajaira) told me. It’s a space that offers refuge, protection, and sanctuary. The Saavedra family provides this through their food and their activism. In many different interviews, Yajaira has said that the main ingredient in La Morada’s food is its activism.

I’ve read how memory, as well as food, are both floating signifiers. Just as memory is more than the different memories we have, food is not only the things we eat. In Eating NAFTA, Alyshia Galvez writes that, “food means a lot more than what we put into our mouths: it is an object of our aspirations and our memories. It is a vehicle for nostalgia, and also for prestige. It is a way that people communicate who they are, the group to which they belong, and who they desire to become” (8). We don’t always remember the same things in the same way: memories, like food, are much richer when we share them. In the Brewing Memories workshops, we reflected on our own experiences, sharing them through illustration, and then consuming them in the form of tea. On October 3 we shared tostadas with guacamole and salad prepared by Antonio and Natalia. On October 24, we broke bread with delicious pan de muerto.

Together, we drank tea and shared a meal around the table. Towards the end of the second workshop, Yajaira thanked all of the participants for showing up and sharing in community—for choosing to spend time together despite all that was happening around us. She said that, as a matter of mutual aid, we don’t all have the luxuries of the rich, or the basic protections like healthcare, but we do all have access to herbs, to plants, and to memories. Every ancestral practice of resistance and organizing—including the practice of sharing memories and indigenous knowledges—has been passed down from generation to generation. Yajaira invited participants to share this knowledge with others, so that they would also learn the benefits of these plants.

In The Human Condition, Hannah Arendt uses the metaphor of the table to describe the world and ‘the public’. For Arendt, the world is not a synonym for planet earth, but instead the space of artefacts and of “work”—a world of things created by humans. It is this world that Arendt defines as a table: “To live together in the world means essentially that a world of things is between those who have it in common, as a table is located between those who sit around it” (52). I think of this image of the world and of a table because of its connection to the public and the idea of an archive in common—of what it is possible to create when we come together, with both our similarities and our differences, and gather around a table to share memories along with a cup of tea.

We build an archive in common by facilitating and sustaining forms of being together in community. The Brewing Memories workshops encourage creation and, at the same time, create worlds, inviting participants to connect with others in the public, recalling memories together in a pandemic context where casual encounters are more difficult to come by. Brewing Memories not only offers a space to document what people share when they are in community, but also, and above all, it creates and facilitates spaces where the community can care for itself and continue to flourish, like plants, so that new connections can take root. Brewing Memories helps to sustain life in common.

--Ángeles Donoso Macaya

Footnotes:

[1] Ariella Azoulay, Potential History. Unlearning Imperialism, 137, 229.

[2] Ibid., 334.