Rethinking Food Justice in New York City

Seminar Meeting on Food Justice

Session one of the Climate Action Lab was devoted to the intersection of food justice and climate justice at the local and urban scale in New York City. It featured remarks by Saara Nafici of Added Value Farms in Red Hook, Brooklyn, and Mychal Johson of South Bronx United.

Both presenters provided an overview of the site-specific conditions of environmental injustice in their respective communities, as well as the creative solutions and sustained struggles with which their organizations have been involved. Shared matters of concern included access to food, resistance to gentrification and displacement, the looming reality of climate vulnerability, and the unresponsiveness of elected officials to the need for a comprehensive planning based in principles of environmental justice and democratic participation. Collective control of urban land (especially through the mechanism of the Community Land Trust), bottom-up democratic planning, and the imperative of connecting hyperlocal struggles to larger scales of movement-building in the interests of social and ecological resiliency were key points to emerge.

Saara Nafici

Nafici discussed Value Added Farms in Red Hook, Brooklyn. Founded in 2001, it is a two-site urban farm project devoted to youth empowerment, community engagement, and movement-building on one hand, and the provision of healthy, affordable food to the neighborhood on the other.

Red Hook is a post-industrial, majority people-of-color waterfront neighborhood in which a large proportion of the residents live in public housing developments, and suffer from, among other things, food-desert conditions (despite the presence of luxury food retailers like Whole Foods). It is also a front-line of land speculation, and is undergoing a massive wave of gentrification and luxury construction. Finally, it is a neighborhood located below sea-level that was significantly damaged by Hurricane Sandy in 2012 and has been given some attention by the city in terms of mitigation and adaptation efforts over the past six years even as the basic geography of the neighborhood is structurally at risk for future climate events. It is a place subjected to the worldwide paradox of the "capital sink": huge amounts of investment going into creating spaces for elite residents at the expense of long-term low-income communities, but which are almost inevitably going to be subjected to flooding in coming years.

Using the two farms and their associated farm stands as a point of reference, Nafici's remarks touched on both the practical as well as affective coordinates of what it means for low-income communities to become socially and economically resilient in the face of climate crisis. Nafici noted the importance of their program not only in providing food to the community as functional urban farm, but also in the cultivation of skills, experience, and leadership among young people, connecting them to city-wide and nation-wide food justice organizing networks that articulate the "hyperlocal" conditions of Red Hook with larger political conditions and struggles of the United States and beyond. Nafici provided numerous examples of the way in which Red Hook itself is effected by extra-local dynamics: right-wing policy shifts in DC have impacted the viability of federal food stamps at farmers markets; De Blasio's housing policies have accelerated gentrification in the area, in turn impacting the demographics and economics of the farm stands; and of course climate change itself as a global phenomena looms over everything that is happening in the area, despite promising developments like assistance from benevolent city agencies to raise the farms themselves several feet above sea level to help with flood absorption.

Finally, in the face of oftentimes alienating and repressive conditions of school and the city at large, Value Added is what Nafici called a "space of joy" for its participants, providing a kind of collective psychic and spiritual sustenance in tandem with the healthy products grown and distributed by the farms themselves. Even so, Nafici conceded that a certain kind of "climate denial" is operative under such conditions for her and her neighbors--not in terms of science or politics, but at a basic existential level of resisting the need to acknowledge that entire areas of contemporary cities like New York might very well prove to be uninhabitable in the very near future. A looming in question in turn is what a politics of "just relocation" would look like in such a context, though this topic was not broached in the session.

Mychal Johnson

Johnson discussed the work of South Bronx United, a long-term environmental justice organization operating on the peninsula of the South Bronx, which encompasses the neighborhoods of Mott Haven, Port Morris, and Hunts Point. The South Bronx is, notoriously, the poorest congressional district in the country, severely underserved by the city and overburdened by ecological risk. For decades, it has been a kind of ground zero for the combined and uneven effects of environmental racism, neoliberal urban development, climate vulnerability, and, most recently, gentrification.

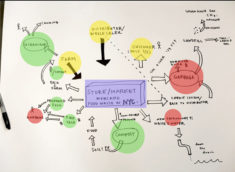

Johnson first explained the hyperconcentration of dangerous and polluting industries in this area, including waste transfer stations, fossil fuel plants, heating oil facilities, and major hubs of the regional food-shipping system. The latter includes the Hunts Point Market, and, most recently, the siting of a gigantic Fresh Direct facility on publicly owned land, with a subsidy of 150 million dollars from the state--a development that has added some 1000 new diesel truck-trips to the streets per day, severely contributing to the already chronic air pollution of this so-called "Asthma Alley."

Johnson detailed the struggles by his group and coalition partners to block the siting of the facility in this area due to its adverse environmental impact, while at the same time amplifying long-term community-based plans for sustainable and publicly beneficial uses of public land such as recreational spaces, waterfront access points, and urban farms. Though a lawsuit brought by SSB against Fresh Direct and the city was not successful in its immediate aim of stopping the relocation, the struggle against it was galvanizing for local groups and helped to highlight the need for an alternative waterfront plan.

Though the South Bronx was not deeply affected by Hurricane Sandy in the way that Red Hook or Lower Manhattan was, it is nevertheless a highly climate-vulnerable area and concentration of polluting industries there would make a flood especially devastating.

SSB has founded a Community Land Trust that has enabled it to steward several pieces of unused public land and protect them from commodified and speculated upon-a piece of highway land has been made into a small urban farm, and an empty building is being converted into a health, education and arts social hub called HART.

Bringing these concerns together is the groups long-term vision of an alternative waterfront CLT that would a) provide recreational green space; b) protect the land from the market; c) provide space for an urban farm capable of truly serving the surrounding food desert (rather than simply adding more pollution like Fresh Direct)' d) create a permeable ecosystem service capable of mitigating storm surges to the peninsula. To this end, the group undertakes waterfront tours, and has worked with numerous entities, including universities, in envisioning what such a multipurpose community-based plan could look like.

Mary Mattingly's Swale

The discussion addressed the following questions:

- How hyperlocal efforts can work at multiple scales, and across/between different groups,

- The potential risk of green space and even urban farming coming to dovetail with the place-making strategies of gentrifying developers, agencies, and populations,

- The affective conditions of activist work under conditions of environmental duress, especially the emotion of despair in the face of seemingly intractable crises,

- How grassroots groups engage with elected officials and electoral politics at various scales,

- How grassroots work has or could productively collaborate with institutions like universities in developing plans, including the prospect of a climate plan?

- How the explicit frame of climate change informs or could inform the work of grassroots work that may not have climate per se as its primary horizon,

- The role of direct action and protest activity,

- The importance of Community Land Trusts as a radical anticapitalist approach to land use that can both fight against real estate powers but also become a tool for imagining resilient urban spaces.

Co-sponsored by the Art, Activism, and the Environment research group as part of the Seminar on Public Engagement and Collaborative Research from the Center for the Humanities at the Graduate Center, CUNY; the Occupy Climate Change! Project of the Environmental Humanities Lab at the Royal Technology Institute of Sweden; and the Climate Action Research Cluster of the Social Text Collective.