On May 10, the Doctoral Theatre Students’ Association presents its 2018 conference, Objects of Study: Methods and Materiality in Theatre and Performance Studies, bringing together working groups of visiting scholars, graduate students, and independent artist-scholars to explore the multiple potential meanings of “object” within theatre and performance studies. In this second part of a two-part blog post, two of the conference organizers Sarah Lucie, and Amir Farjoun, both students in the Ph.D. Program in Theatre and Performance—reflect on some of the questions about materiality and knowledge that arise in their field, and the particular challenges theatre and performance studies might offer to object-oriented thought. Click here to read Part 1 reflections and thoughts by conference organizer Eylül Fidan Akıncı.

Portions of the conference are open to the public; due to limited seating, please RSVP here before May 8th.

"Performing Human/nonhuman Relations”

-by Sarah Lucie

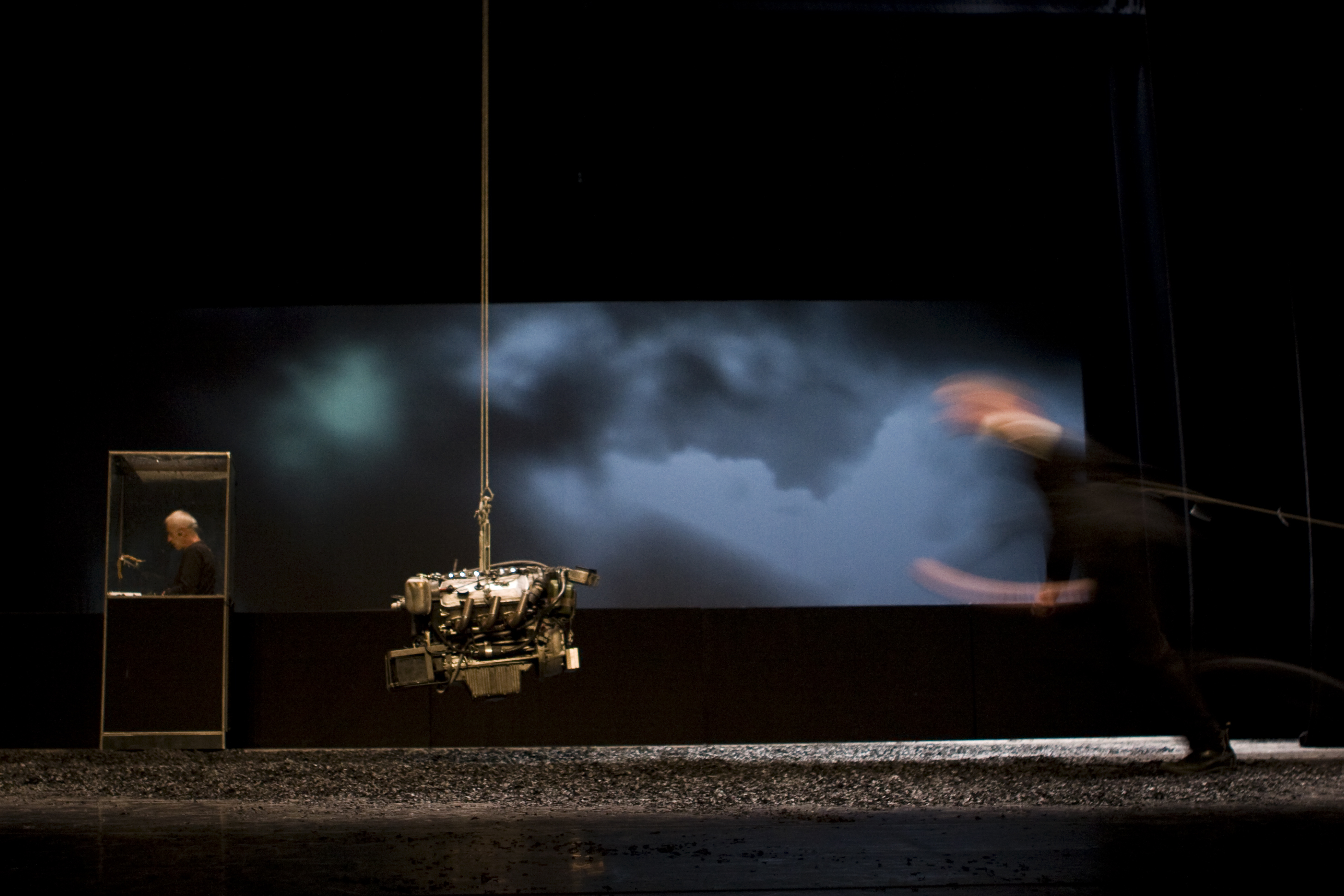

I believe that the defining elements of theatre as a live art lends the theatre genre to real practical and theoretical engagement with the notion of an object’s ontology, and its active relationship with the human. As Eylül pointed out, theatre differs in form from the visual arts in that the human agent is visible and celebrated within the theatrical network of production. In visual arts, the objects perform, but in some cases, these performances are communicating the trace of the human artist, while in others, they interact in part through aura. In theatre and performance, however, the audience watches the materiality of the object perform in tandem with the materiality of the human body.

So much of Object Oriented Ontology and new materialism is asking about the ontology of the object, and even the perspective of the object. But one of the major motivating factors behind this mode of inquiry is precisely to reconfigure the relationship between the object and the human: make the human humble, more aware, more in awe, more respectful, more sensitive, more responsible. OOO’s developing conception of an object shifts from something contained, passive, inert, and definable into something withdrawn, active, and with multiple layers of history and being that are unknowable from an outside perspective. This new definition is important because it would mean that a human is an object, too. But not in a silenced, objectified way. Rather, the definition is raising up the object into something complex and active, something incapable of being objectified.

Object studies is therefore very much about the human—and this is where theatre comes in. Theatre exists in a shared space and time, where the artists, objects, and audience are working together to communicate and create meaning. In theatre, the object’s sensual qualities are communicating through affective means, functioning in much the same way that the human actor’s sensual qualities are honed and mobilized. You can’t know the entirety of either the human actor or the object actor, and both require an audience to receive their meaning. Studies have found that performing objects—the more literal kinds such as puppets and robots (both humanoid and not)—function on stage in the same style of mimetic representation. The audience will relate to, empathize with, project onto all equally. In some cases in fact, it’s perhaps even easier to project onto the performing object, since it’s a simpler device.

Theatre is as much about the human in the audience as the human onstage. It is a space where subjectivity is formed, made even more powerful in that it is a communal subjectivity. The nature of theatre, therefore, makes it a site in which the sensual, active qualities of objects can be practically tested and experienced, where questions about the subject/object divide can take front and center stage.

Theatre’s liminal nature also suggests, in a more utopic vision, that perhaps the changed nature of the relationship between the human and the object within the theatre space might “spill out” to affect this relationship outside the theatre space as well. As in ritual, when you exit, you have changed since the time you began. What change—within us as well as in objects—might theatre bring about?

"Theatre and the De-Objectification of Knowledge"

-by Amir Farjoun

I’ll start by repeating and paraphrasing both Sarah and Eylül: before a reOrientation towards Objects and their Ontology, the defining assumptions of the field of theatre and performance studies contend that the “object of study,” so to speak, is no object at all. An anti-object indeed. To study a live, interactive act is to study a phenomenon that is not only ephemeral, momentary, and always-vanished, but also fluctuating, transforming, and never completely documentable—that is, never completely knowable. If there ever was a field designed to study non-objective or non-objectified phenomena, theatre and performance studies is probably it. So why then ask about the “object of study”? Shouldn’t we, ephemerality junkies that we are, just leave it alone?

I agree completely with Sarah’s claim that objects’ renewed modes of being necessitate a reconfiguration of the human, and moreover, that the theatre is (or at least should be) a place to learn, experiment and implement such reconfigurations. And just as new ways of being prompt a reconsideration of the human, it might push the understanding of what a theatre actually is away from an architectural or institutional understanding and towards the very act—the intellectual, critical act—of staging being (or ontology). This is why a conference about “objects of study” is, to me, a conference about our own practice of theorizing (read: staging) what is, considering its intense and somewhat frustrating lack of stillness.

Unproblematized objectivity, not just of things, but of thoughts, texts, events, is assumed regularly, if only for the sake of argument or understanding. Seeking perhaps to reassure ourselves of the stability and sustained presence of these objects of thought, we adopt objective or objectifying tones, positions, and terms. In our books, in our articles, in our thought, time often stalls. When they’re not ignored, affects and emotions, too, are objectified and stabilized, because, it seems, we can study only what is still and stable. Even when considering performance, and even when dealing with the recent re-Orientation of Ontology, thinking begins with identifying and objectifying something into an Object Of Study. In so many (many!) words, we point and say, “Look, an OOS!”

But one must admit that objectifying complex study practices and relations offers very limited options—genres or dramaturgies—to the staging of what is. This theoretical theatre is traditional and strictly conventional: An (objectified) object of study shall be probed and mapped; its features indexed, compared and ordered; its meaning extrapolated and duly articulated, processed and filed. Curtain… Applause. Clearly, this theatre of knowledge can only tell one tale, an accumulatory myth of progress: more objects, seen more closely and/or broadly, produce more knowledge—and the more the better. But asking about the “object of study” in performance means also to question the necessity, and the price, of this compulsive objectivity in the practice of studying. What other knowledge-theatres are barred from existence because of these patent theatres of convention? What other theatrical models might inform our relations with staged “objects”? How might knowledge feel when the object of knowledge is allowed to affect us, and we are allowed to reciprocate? To ask, then, about the objects (of study) in the context of performance resonates as a call to dramatize the act of study, and to implicate ourselves more consciously and bodily in this lively staging.