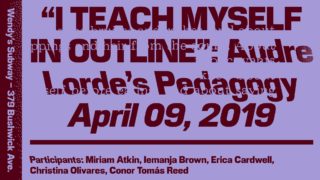

The Center for the Humanities at The Graduate Center, CUNY seeks to build on the legacy of radical, de-colonial, anti-racist pedagogies at CUNY. A former CUNY educator, Audre Lorde’s teaching methods and practices are central to this legacy, and her vital work as a poet and activist continues to model survival and living for Black / queer / feminist readers. Following from the publication of a selection of Lorde’s syllabi and other teaching materials in Lost & Found: The CUNY Poetics Document Initiative, co-facilitators Jillian Lane White and Conor Tomás Reed formed the Audre Lorde-focused reading group “Your Silence Will Not Protect You!” Throughout four sessions, this group of twenty participants approached Lorde’s work from their own experiences, applying the power of her teaching / writing / radicalism to the process of elaborating study in community. This group was sponsored by a Humanities New York Reading & Discussion Grant, Lost & Found : The CUNY Poetics Document Initiative, and the Center for the Humanities.

Below reading group member Spencer Garcia discusses their experience reading Lorde's work in the group.

* * *

When was the last time you shared your comfort foods with strangers?

During our first gathering, Conor and Jillian invited us to share our comfort foods with each other. As introductions wound around the room, people openly spoke about the foods that soothe them, and generously gave insight into the moments that this nourishment was needed and cherished. This collective act of sharing prompted a further discussion about what brings us comfort, and why we may not vocalize these things with others, especially strangers. While our favorite foods are more commonly shared during icebreaker activities, the offering of our comfort foods to strangers can feel more vulnerable. As revealed in our discussion, such foods can be connected to our cultures, chosen families and families of origin, specific memories or periods of time in our lives, and often assume a deeper meaning in why and how they bring us comfort. Maybe we don’t usually share our comfort foods with strangers because we’re worried about what this might reveal about ourselves, or maybe we just don’t share because we’re not asked.

From this initial conversation, our reading group cultivated a sense of openness and trust with one another that would have taken weeks or months to create in other spaces. We could (and probably should) credit our collective trust and vulnerability to the magics of the universe and Audre Lorde for bringing us together, but Conor and Jillian’s dedication to creating a space that centered Black queer women, and other queer, trans, and non-binary people of color truly enabled the growth of a community. Conor and Jillian’s intentionality in developing this group [1] signals the deep importance and value of reading, discussing, processing, and feeling Audre Lorde’s poetry and essays in community. What began as a reading group has transformed, and continues to transform, into a dynamic community of Black women and queer, trans, and non-binary Black people and people of color who share a love for Audre Lorde (among many other things). Since the official “end” of the reading group, there have been more meetings, Friendsgiving and New Year’s Eve celebrations, events attended together around New York City, and plans to continue reading, meeting, and growing with each other.

“So it is better to speak / remembering / we were never meant to survive.”

--Audre Lorde, “A Litany for Survival”

During our first session, we dove into Lorde’s “A Litany for Survival,” “Poetry Is Not a Luxury,” and “The Transformation of Silence into Language and Action.” Our discussion largely focused on the tensions between choosing to remain silent or speaking up and taking action in the spaces that we were “never meant to survive.” Continuing the generous practice of sharing ourselves and our stories with one another, several people offered their personal experiences in their current and former workplaces and academic institutions. If we were never meant to survive in these spaces, let alone expected to even enter them, did this allow us more freedom in speaking out and taking action? Did this mean that we had less or nothing to lose?

Since this conversation, I’ve been reflecting on how to balance naming my pain, practicing self-preservation, and attempting to make tangible change. I’ve thought about how to navigate these choices in community and what it means to put myself into potentially harmful situations in hopes of making them more bearable for myself and others. In “The Transformation of Silence into Language and Action,” Lorde writes “My silences had not protected me. Your silence will not protect you.” Expressing our pain and suffering in a society that thrives on silencing us can be as powerful as it is dangerous. In naming our harm, we can cause damage [2] to the people and structures that seek to subordinate us; however, those who have harmed us can just as easily retaliate, and perpetuate further violence. [3] There is so much possibility for liberation in naming our pain and taking action, and there is just as much risk.

“What I most regretted were my silences. Of what had I ever been afraid?”

--Audre Lorde, “The Transformation of Silence into Language and Action”

Many times, when I have chosen to speak out in reaction to oppressive behavior, my pain and the pain of other people harmed has been ignored, or I have experienced retaliation for bringing attention to the issue. However, while rare, there have been moments when taking action led people to take accountability for their behavior. In our discussion of “The Transformation of Silence into Language and Action,” multiple people shared moments of speaking up against oppressive behavior in their workplaces, academic institutions, and communities, and how this practice was essential to their self-preservation and survival.

One person offered that sometimes it’s enough to speak and break the silence, and that you don’t have to stay in a toxic environment to see the work [4] through. Rather than continuing to endure harm, leaving the situation can provide an opportunity to begin healing and focus on transformative justice for yourself and other impacted people in the community. This is something I personally struggle with—speaking out but not taking action—however, after participating in this discussion, I think that this approach to injustice and violence can serve as an incredibly powerful tool of self-preservation for queer, trans, and non-binary people of color, and especially for Black queer and trans women.

* * *

I first encountered Audre Lorde during my undergraduate studies at Vassar College, but this reading group has granted me the opportunity to revisit her essays and poetry with an entirely new lens; (re)reading Lorde in this context has allowed me to reflect on her work and my life in ways that I never had the space to in the confines of a predominantly white institution. As our reading group continues beyond the CUNY Center for Humanities, I’m excited to continue our individual, interpersonal, and community growth with Lorde’s guidance, and to honor the foundation that Conor and Jillian lovingly created for all of us.

--Spencer Garcia

[1] When Conor and Jillian sent out the call for participants, they included the following language: “This reading group is open to all. However, we will intentionally center the participation of people of color; specifically women, gender non-binary, and LGBTQ people. Participants who do not identify with these groups are asked to be mindful about not eclipsing the experiences and participation of those being centered. We also ask that people with access to resources and institutions where Lorde’s work is regularly available pass along this announcement to friends, family, and community members who may not.”

Additionally, Conor and Jillian asked for people to request to participate in the reading group by filling out a short Google form. Through these questions, Conor and Jillian generously encouraged potential participants to critically consider our involvement in the group, how we could contribute to the space, and how we could take or create opportunities to engage with Lorde’s work depending on our own (previous or current) institutional and financial access.

[2] Here, I use “damage” to mean the dismantling of interpersonal and institutional behaviors of anti-Blackness, racism, homophobia, transphobia, misogyny, ableism, classism, and all other systems of hierarchical power and subordination.

[3] This violence often takes the form of punitive actions such as demotion, firing, or disciplinary action in the workplace, suspension or forced leave in academia, and other actions that greatly diminish one’s livelihood.

[4] I want to complicate notions of what is and isn’t considered transformative justice work within the context and confines of academic institutions and the workplace. Naming injustice and violence within these institutions is “the work,” because this action inherently generates opportunities for transformative justice, institutional and interpersonal change, and self-preservation and healing.