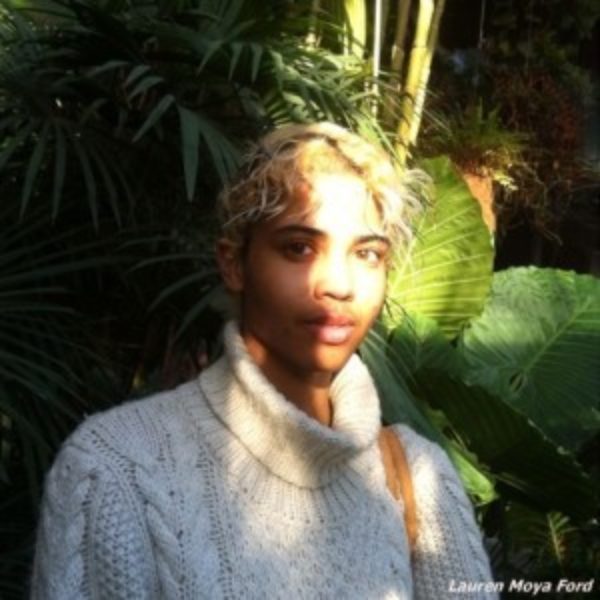

In anticipation of her New York Chapbook Launch at Berl's Brooklyn Poetry Shop on April 11th with Major Jackson, we got in touch with Layla Benitez-James to celebrate the release of “God Suspected My Heart Was a Geode But He Had to Make Sure,” winner of the third annual Toi Derricotte & Cornelius Eady Chapbook Prize from Cave Canem. In the following interview, Benitez-James shares her thoughts around the compulsion to collect, turning over ideas of desire, and the entangled holiness between a portrait of Jimi Hendrix and the Virgen de Guadalupe.

Stephon Lawrence: This chapbook was originally titled Moth & Rust, what inspired you to change the title and how has that change affected the work as a whole?

Layla Benitez-James: I moved to Houston in the summer of 2011 and had about a month free before starting the creative writing program at UH. I was rereading a lot of books I had brought with me in the move, and it must have been in Paradise Lost where I came across some quote which led me to the biblical passage Matthew 6:19-20:

Lay not up for yourselves treasures upon earth, where moth

and rust doth corrupt, and where thieves break through and steal:

But lay up for yourselves treasures in heaven, where neither moth nor

rust doth corrupt, and where thieves do not break through nor steal

I've never been able to come across what passage it was again (perhaps it actually was from Dante's Inferno...) but I absolutely loved this idea. As advice and law, I loved it partly because I lived my life in such an opposite way. I am part magpie both when it comes to writing and in my real life. As a kid, I was always collecting pretty stones, feathers, shiny pieces of trash...I have this compulsion which has never left me where I want to collect and save any little thing I find pretty...now I try to keep them in my journals, pasting movie stubs and pretty fruit stickers to contain the clutter a bit.

Coming from Texas with all its mega churches, I also found it interesting to think about that discontinuity between how people live and this idea that rich men actually can´t enter heaven. I also love the orange-rust or red-rust color, and the rainbow of muted colors that moths come in. Basically, Moth and Rust was a personal shorthand for ALL these ideas, and I was really attached to it until I realized that the poems needed to do the work of unfolding these images and concepts themselves. All the wonderful baggage I had around the phrase was not necessarily being translated to a reader. I saw it cropping up more and more frequently and realized it was not actually so fresh as it seemed to me at first (I later discovered the journal Rust + Moth and thought, ok, I need to make this more my own).

The title poem had become my favorite for some time and had kept moving up in the manuscript order. That title itself had been a bit of a placeholder; when I wrote it, it was just for me, just what I wanted, but I thought it was a bit too eccentric and even too melodramatic to be taken seriously. But I kept stalling on writing a “real title” until finally I just accepted that that was it and that loving it myself was enough. On my final reorder when I put that poem first I realized part of my obsession with objects was also about breaking and return and came across a note in an old journal about the poetry collection Tell Me Again How the White Heron Rises and Flies Across the Nacreous River at Twilight Toward the Distant Islands by Hayden Carruth. If that title can exist, I was willing to take a leap with mine. The work as a whole was then just catered a bit more to my own eccentric tastes, and I weeded out a few poems that were a bit quieter.

SL: We often think about chapbooks—the objects themselves—in a couple of ways: as these very self-contained things, or as a piece of a larger project or book—a small encapsulation of what we are thinking and writing and working towards. How did these poems come together for you as a chapbook—what made them fit together in this way?

LBJ: When I think of self-contained chapbooks, I think more of project-based books where all the poems are unfolding out of some central theme or exercise. This project is certainly part of a larger project or really more of a collection of poems, which were fit together but in some ways remain very separate; they are what survived from a very harsh weeding process.

Every few years I try to make a huge document, a real collection, of everything I've written to see what threads are going through and which works might go together. For this particular manuscript, I was concerned with poems that turned over ideas about desire and objects but wanted to think about desire in a very broad sense; the desire here is directed at objects and people but also spills over into abstract concepts like death and creation.

Evolving out of that ‘moth & rust’ quote, I latched on to two other quotes so that I had these three:

Lay not up for yourselves treasures upon earth,

where moth and rust doth corrupt.

Matthew 6:19 (KJV)

Show me any object, I’ll show you rust on a wave.

James Galvin

But then you must never forget that every object has its passions.

Francis Bacon

In part, it was about following the threads of all those desires that won´t really, or shouldn´t really, fit into heaven, and also about finding the connections between physical objects and abstract concepts. All the poems that were inhabiting that space stayed in, but it definitely feels like a part of what I´ve been writing and working towards.

SL: There are these elements of religion and religious imagery throughout your work—God, snakes, foxes. In fact the title poem, “God Suggested My Heart Was a Geode But He Had To Make Sure,” reads to me much in the way of the creation myth, with the repetition of “this was good” and “good, God said” and the way the title suggests an extra level of care being taken in the forming of your heart. What role does religion take in your writing, and how does it flow with the more magical elements of your poems—moments where you (or the speaker) are the conjurer, the creator?

LBJ: It's funny, I was not raised religious but have really latched onto biblical language and imagery. Partly this is the influence of an amazing and devout Grammy, but at university I took a class on the Old Testament and felt like my parents had been holding out on me. In elementary school, apparently my teacher had to ask my parents “what we were” because I didn't really know and we were approaching the time of Christmas vs Hanukkah vs Kwanzaa. I had informed her I was a pagan, as it was something my dad had said.

I suppose despite the fact that I didn´t get a really formal (strict) religious education early on, I did get a sense of things being holy. My dad loves Jimi Hendrix and had pictures of him all around the house. My mother loves the Virgen de Guadalupe, and our dining room had facing walls full of pictures of both so that it actually took me a minute when I was older to detangle the two. I had religious imagery, but it was really specific to my household, I remember one image of Hendrix had those same rays of majesty streaming out behind him as the Virgen de Guadalupe and as a kid I did not yet know how to distinguish more traditional images from those riffing. Even now my dad would deny any questioning of Hendrix´s (or Saint Jimi's) holiness and got in trouble with his mother (I think before I was even born) for teaching my older sister to make the sign of the cross any time someone mentioned his name. But perhaps this makes me wish to mix more magical elements of my poems with more traditional religious imagery, or the mix feels really natural to me.

I've long been obsessed with snakes; the snake is my Chinese year symbol, and growing up I always wanted one as a pet. I find them ridiculously beautiful, but it was also woven into my childhood and life in Texas to look out for them. Foxes play a similar role in my psyche; I have long been obsessed with them as lovely creatures, and they were also a treat to see and associated with getting out of the city. On a very basic level, these animals were just part of my world, and it has only been later when I've thought about how loaded the image of a snake is, especially when coupled with other religious imagery and language.

You are absolutely right about the “good” coming out of the creation myth, and I truly love creation myths in general. That title poem came out of the first time I was really considering anything like a higher power in any sort of serious way. I had gone on a trip with my family to Cuchara, Colorado, and in the house we stayed in was a copy of Diné Bahaneʼ, the Navajo creation myth, which I read while pretending to fish. Fishing was a family activity, but I really don't like stabbing anything through a hook or having to take fish off a hook, so I would bait my hook with a leaf and read this book and draw. There are bears there, and so there was also this constant feeling of needing to look out, (they have their dumpsters electrified there, which I don't think is any way to live) but it did make me think about everything being created, the good and the bad, and an attempt to look at both with some sort of equal weight.

Part of what draws me to creation myths is this search for answers and the idea of giving someone an Answer to unanswerable questions. I think the similarities in myths around the world are also really beautiful. Many place water first and have this concept of a god who is in this constant battle of making and correcting mistakes; none of these creators are getting things right on the first try, and their mistakes become the explanation for all kinds of things.

SL: In your poems, I also see occurrences of the natural, supernatural, and spiritual all interwoven in this really beautiful way as you bring us through moments of creation and destruction. These unstoppable forces, framed against the fragility of the body. I saw this particularly in bodies of water—pools, the ocean, rivers—and it made me think about the way blackness holds this very interesting space throughout your poems. There’s the almost inseparability of black bodies and bodies of water—our ongoing histories, and traumas with it—you say “Even as you are standing/ on the banks of my river/” in “Desperate” and “...I see/ how one drop of black/ can weigh more/ than the sea of white which/ surrounds it…” in “Shutters Shut & ()pen As Do Queens.” Considering the religious aspects of your writing as well, do you see the bodies of water as both spaces of cleansing and revival as well as spaces of death and destruction? How does the multiplicity of water factor into your work?

LBJ: I didn´t realize how much water is in the book! That must come with the creation myth obsession, but it is exactly the marriage of creation and destruction within bodies of water that keep me returning to those images. It´s interesting too that those lines you pulled out both come out of other works that I´ve paraphrased; the first comes from Things Fall Apart but was reintroduced to me in a really roundabout way. An artist in Paris who is a friend of a friend was trying to discover the origins of that phrase as he wanted to use it in a show, but it had been used to describe the motivations for looting (a loaded word, justified gathering outside legal norms would be another way to call it) that were taking place in France:

The topic that day was the rampant vandalism unleashed by poor youth in certain French cities. Young men who traced their roots back to places like Algeria, Morocco or Senegal, and who lived in slums outside the cities, had a habit of celebrating New Year’s Eve, for example, by going down to the center of town and setting cars on fire or smashing storefront windows. Lyon had a lot of this kind of vandalism, so Louai knew something about it. I listened for a while, then could not help making a comment: how useless that kind of random violence is, how it could never make things any better for those young men.

“Why do they do it?” I asked. He assured me it was hard to understand how difficult life can be for people of color in the French banlieue. Then he quoted a line from a novel that would stick with me: “I cannot live on the bank of a river and wash my hands with spittle.”

I am still untangling all the intersections between black bodies and bodies of water but M. NourbeSe Philip´s Zong comes to mind as something that was humming in the background. Inseparability is a good way to think about it. There is so much unexamined cause and effect in our ongoing histories, and I think a lot of being drawn to images of water is still unconscious in my creative process. I am living in a seaside town for the first time in my life, but there has also been so much pain and loss of life in the Mediterranean that it has felt like a very fraught blessing at times. Part of the ¨drop of black¨ quote comes from a novel I translated, Hombre en azul by Spanish poet Óscar Curieses which imagines a newly discovered diary of the painter Francis Bacon. A line talking about color contrast and proportion was instantly pulled into my own black american context as I thought about the one drop rule and was transported back to Ellison´s Invisible Man and the main character´s time in a paint factory, trying to make the whitest white.

SL: You close the chapbook with a poem that is strikingly different in form but that encapsulates this work in such an exciting and holistic way. With the incorporation of kintsukuroi, you bring home the idea of mended flaws becoming part of the object, or body, and it being more beautiful for it. The cracks and seams—the scars—becoming symbols of perseverance and not solely destruction (though it doesn't leave the memory of that destruction behind either). It speaks to the way in your poems these kinds of returns are constant. Bodies are damaged, then rebuilt, rebirthed—ash to soil to ash again. I was particularly struck by the power of the last lines: “if (you are the earth and you are the den and you are the red roots/ coming/ in,/ then (what is worse:/ the pure, pink, helpless death?/ or you reaching through/ yourself/ to hold it?)/ else/ return;/ }” Can you speak a bit about these lines and the decision to close with this poem?

LBJ: I love this reading of the poem as it gets at just what I hoped it would/could do, but in a form that is a wild digression from the rest of the book and is a beginning for future experimentation, a bit of where I want to go. The form is my own invention, inspired by a very difficult semester of computer programming taken for a science credit at the end of my university experience which has never left me. By some divine miracle, there were no computer programming majors taking the course, and our professor was pregnant, which meant that the course could be just slightly less rigorous and that it could finish a month early leading up to her April due date. I still feel grateful to that kid, who must be about 8 years old now, for coming into the world when she did because the inner workings of computers absolutely brutalized my brain. But the class also let me into a really important understanding of what computers really are and offered up a kind of new creation myth in and of itself. In the beginning there was a kind of black void, and the word, code, had to come in and organize it. As my brain attempted to learn lines of code and digest this new language, I gained a new appreciation for icons on a desktop which look like recognizable objects and the fact that, by double clicking on one, I am able to skip writing lines and lines of code and utilize a thousand short cuts to navigate computers and the internet. In Don Quixote, translation is described at one point as seeing a tapestry from behind, where you don't quite get the polished picture but all the strings and messy crossings that show the process, and I feel this too is what learning to code was like when before I had only known the polished exterior and was for the first time getting beneath that.

I've had an essay in the works about it after feeling like the poem as machine idea needed an update, but also just the look of organizing my ideas within these constraints; in C++, which is what we were learning, you are supposed to have a heading which describes what your program does, and then include all these parameters. You also can set up these cause and effect relationships, and it just seemed to translate really well into holding poetic language instead of code...though at UH I had a professor that sent an email out to the whole class asking for ¨more wildness please¨ and when I brought in the first ¨program¨ poem he let me know that he had not really meant for me to get more wild and that the form was a bit too much. I've gotten mixed responses, but I love it and especially love that the programs always end on ¨return.¨ Badly written code will also return errors; your computer will give you a list of things you need to fix in order for the program to function; these poems as programs will always ¨return errors¨ and that to me was also the beauty of something like kintsukuroi (one of these bowls appears in Lemonade which is what gave me the idea for the object in relation to human breaking and repair) in that the poems give me a way to trace my errors and hold onto them in a beautiful way.

Now connecting that with the creation myths I realize that may be another reason I'm so drawn to that kind of language; I’m thinking now of the Koran as well, which I read parts of in Spanish as part of a medieval Islamic literature class in Madrid. All the religious texts I've read so far seem to make beautiful lines and stories out of mistakes and frustration, out of wars and transgressions. We try to create these metaphors for how we are feeling and the ways in which we fit into the world, but in the end, we are each a piece of the metaphor. I suppose it's a bit like trying to say we contain multitudes or acknowledging that all the people in our dreams are really just different parts of our own brain firing back at us. So there is this idea of death and different ways to look at it, some more melodramatic than others, but in the end it's all in my head, all the images and metaphors I use to try and explain things to myself eventually must be shaken off so that I can just get on with life, a kind of reminder to reach for the right things.