Short description:

Practicing Distance is a multi-part guide for preparing for our futures together post-quarantine. In each part, Jeff Kasper offers a series of short practices, beginning with an introduction on four proxemic distances—intimate, personal, social, public—then facilitating guided creative exercises to engage with solo or with a partner in imagined physical proximity during the time of the pandemic and beyond.

Content Warning:

Is this for me?

Maybe or maybe not. The content of these exercises may not be for you at this time. The practices offered are not created from a clinical perspective, therapist, or counselor, and instead have been developed by artists for peer-support, community building and educational purposes. Some require comfortable participation in intimate conversations, guided reflection, and consent-driven closeness with another human. As mindfulness activities can be deeply challenging for many folks navigating the potential of dysregulation, please note that these activities are based in guided––rather than unguided––methods grounded in trauma sensitivity. Opt out of any interactive or contemplative material that feels unfit for you, at any time. Come and go as you please. You are the expert of your own body mind.

For more context, see Introduction.

Social distance [4-12 feet]: being together doesn’t always have to mean compromise

Social space—the spaces in which people feel comfortable conducting routine social interactions with acquaintances as well as strangers.

Have you wondered why public health officials are using the term “social distancing” even though it seems like a bad choice of language and sends a negative message, as opposed to the more accurate “physical distance”? We are more familiar with the term “quarantine,” which, in modern memory, was a prevalent practice of the restriction of the movement of people during the 1918 influenza epidemic. The term “social distancing” was most recently used by governments in 2003 during the SARS outbreak, almost as if attempting to lighten the appearance of a carceral or punitive state with strictly “neutral” scientific language. The resulting use of social vs. physical distancing wrongly suggests a suspension of sociality instead of a more logical re-emphasis on widening spatial proximity to avoid spread of illness. The term comes directly from social science of proxemics.

Social distance as a literal physical distance is used in business transactions, meeting new people and interacting with groups of people. Though we are familiar with the demands to “stay six feet apart”—4 to 12 feet is the large range of distance that physically constitutes “the social” in Edward Hall's proxemic social distancing. Social distance may be used among classmates, co-workers, or acquaintances. Generally, people within social distance do not engage in physical contact with one another. People may be very particular about the amount of social distance that is preferred. Some people may require much more physical distance than others. This also varies widely across culture, subcultures, and contexts. Whereas some cultures might include the possibility of physical contact within comfortable social distance, in other cultures––think of an uncrowded sidewalk in New York City or a common commercial space––if a person comes too closely, the individual is likely to back up and give themselves the amount of space that they feel more comfortable in.

Social stories for navigating conflict

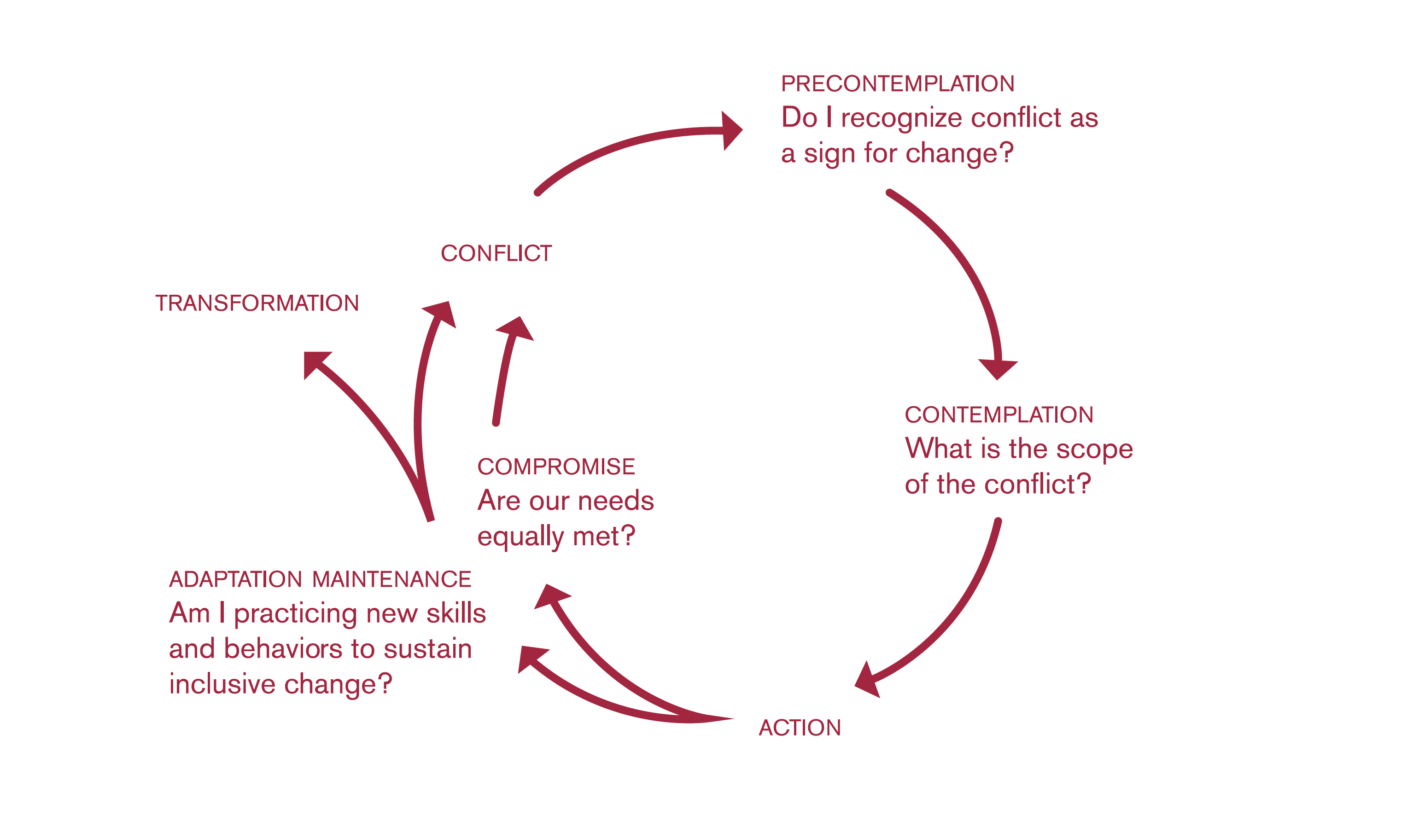

Though many of us learned that conflict is bad or that it is universally unsafe or a negative experience—avoiding conflict undermines cooperation, collaboration, and mutuality. Moving through conflict with honesty—prioritizing care for our needs and feelings and the needs and feelings of others—can bring us closer together. We learn to avoid conflict as a strategy for surviving instances when we are powerless. In order to shake this, we need to imagine and practice new strategies, so that we can get our needs met, be honest about how we feel, and build deep relationships (of all kinds) with others.

“Social stories” and interaction scenarios are a learning tool used often by neurodivergent youth with their caretakers, parents and educators. They are an exercise in concrete thinking and a survival strategy—an example of crip ingenuity in a disabling world. Social stories can be important tools in articulating one's personal boundaries and approach the context of physical distance and giving and receiving care—especially during conflict. Try out writing and playing out a conflict story.

[Download the PRACTICING CONFLICT worksheet here]

In 2 sets of pairs (4 players), create and practice a common conflict scenario by following these steps:

1. Invent a scenario where there is a common conflict within a small group of 4. Spend about 15 minutes coming up with your story. (See example scenario narrative for inspiration.)

2. Choose a role.

role 1:

played by:

role 2:

played by:

role 3:

played by:

role 4:

played by:

3. Now decide who will initiate the group conversation to address the conflict, and work together to come up with a script. The objective is to seek a cooperative solution that is transformative and inclusive—a solution that does not generate an unwanted compromise. (25 minutes)

In a cooperative environment, each person finds out what the other needs, and both work together to meet those needs. Like in any relationship, parties may decide to compromise.

But without collaboration, compromise involves someone leaving the conflict with only partially fulfilled needs. In other words, this is not about coming up with a solution that benefits only one person—it should feel right to everyone involved. If you are struggling, don’t forget you can pivot and move in a direction that seems unexpected.

Imagine yourself in-role by answering the following questions:

How do I feel?

Why do I feel this way?

What do I need to move past these feelings?

What are the goals or intentions of each character in-role? (Think of these as shared goals or important details that transcend your needs and are articulated for the collective good.)

Here is a script that will help you get started:

I feel .............. because .............. I want to know ...............?

4. Now for 25 mins, listen to your group’s point of view, and transform the conflict from there! Discuss with your partners possible transformations. List them below and circle the best choice:

----------------------------- ------------------------------ ------------------------------

----------------------------- ------------------------------ ------------------------------

Notes and Reflections:

Did you compromise?

If so, how do you feel about the compromise? Did it benefit your needs and your partner’s?

What was the end result?

Scenario Example:

I once encountered a scenario that illustrated the difference between good and not-so-good compromise beautifully: Two art students had access to shared art materials, namely a pad of Bristol paper left over from last semester, and each of them wanted it. The second year drawing student claimed she should get it because she’s more likely to use it for her works on paper. The third year sculpture student thought they should get it because they had spent more money on tuition being a year older and should get first priority because of lack of income. They decided to split the pad of paper in half, and both were pretty happy at the decision. However, after they parted, one of them used the paper for a drawing project and threw away the front cover. The other used the back cover for a sculpture base and threw away the loose papers. They both ended up running into each other at the art supply store to get the remainder of material needed and wasted. Had they just talked about what each of them needed, they could have fulfilled their needs entirely and not generated any trash or need to purchase more materials. This is an example of compromise––each person walks away with their needs partially met, so as to end the conflict. But, wouldn’t cooperation be better? In a cooperative environment, each person finds out what they other needs, and both work together to meet those needs. So, remember this the next time you’re tempted to compromise without finding out what the other person REALLY wants. Who knows? You both may leave with fulfilled needs. And, wouldn’t THAT be the best option?