Via this series of interviews, Distributaries seeks to sketch out the contours of the public humanities ecosystem—the centers, institutes and initiatives undertaking the work of the public humanities—at the City University of New York. Apart from sharing the specific work these programs and centers do, we also wish to offer up their visions of the ‘public humanities’ as a field, and the rich ways in which the ethos of this term is realized.

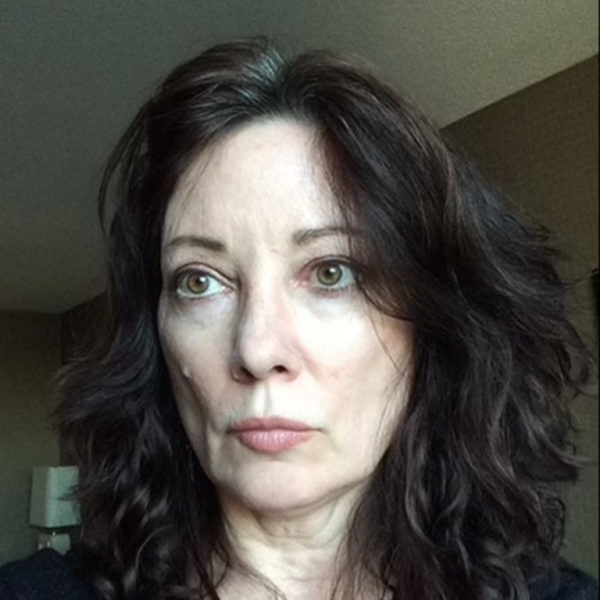

In this interview, I speak with Linda Martín Alcoff about her role as co-director of the Mellon Public Humanities Program at Hunter College. Alcoff believes in encouraging students to think about publicly engaged work early in their educational trajectories, while also emphasizing that publicly engaged humanities projects are not necessarily funnels into graduate school—but they also set one up well for a range of compelling career paths.

–Queenie Sukhadia

Queenie Sukhadia (QS): How do you understand the term “public humanities”?

Linda Alcoff (LA): Recently, we received a large Mellon Foundation grant for public humanities at Hunter. We spent the first few months with our faculty design committee exploring the meaning of the term. Not only because not all humanities faculty are familiar with it but also because there are different ways in which the term has been defined. For the purposes of our program, we decided that we were going to define it in terms of publicly engaged humanities research and scholarship.

To be clear, we don’t think that all scholarship is publicly engaged; nor do we think it needs to be. We absolutely want to support the flourishing of areas in the academy that aren’t engaged with public issues. But there’s a lot of scholarly work in every department in the humanities that is in fact engaged with public issues. And by public issues, I mean issues that the broader public, outside of higher ed, is aware of and concerned with. The broader public is aware that we have a climate crisis, a policing crisis, a racism crisis, a crisis about what to do with monuments, just to give some examples. Broad publics are already aware of these controversies and may have an opinion about but also some questions. So, the public humanities really refers to humanities scholarship and research that’s engaged with issues that are already visible in the public domain—usually crises and controversies. That’s how we decided to define publicly engaged work in the humanities.

The public humanities really refers to humanities scholarship and research that’s engaged with issues that are already visible in the public domain—usually crises and controversies.

I think the second component of this concept of public humanities is that the work done should engage with broader publics in a meaningful way, to the extent that’s possible. There should be a conscious and intentional effort to go beyond academic journals and publications to engage with broader publics.

This is an issue because universities tend to peddle to younger scholars the idea that the only work that counts is publications in top-ranked peer-reviewed journals. So, the writing that one may do for a newspaper or a newsletter, or work that one may do on a panel or for a community center are not as valuable. These other kinds of publicly engaged work have typically been invisible when one applies for promotion or tenure, or even for a job.

There’s been a movement within the academy that I’ve been a bit involved with for the past twenty-five years to change the terms of tenure, and include a fourth category alongside the usual categories of scholarship, teaching, and research. We need a fourth category for public engagement. The writing that one does in broader non-academic venues, the activism that one does, one’s engagement with community organizations—they’d all be listed here.

I have a former student who has done a lot of work on gun control. He tried and, in fact, came very close to getting gun control passed in the Colorado legislature. He’s also written a book on gun culture and masculinity. So, his activism really informs his philosophy; it isn’t extraneous to his scholarship.

This movement doesn’t argue that every faculty member has to have something on their CV that falls within this category of public engagement. There may be faculty members who don’t and that’s fine. We don’t want to make it mandatory for all, but we want to make sure that the university does recognize and value faculty members who are engaged with broader publics. We’ve also argued that such work can, in fact, be judged—just like we judge the quality of scholarship, teaching, and service. So, it’s not that we’re dropping our quality controls for hiring, promotion, and tenure, but that we want to expand the kinds of work that the university should value. And, often, this is work that is already being done by many faculty that’s invisible when it comes to promotion. It is also the case that many faculty of color and women, immigrant, and LGBTQ faculty are the ones most likely to do publicly engaged scholarship. My students are Hunter are sometimes hesitant to go into fields that they feel are irrelevant to their beleaguered communities; they want to maintain ties and provide some help in the form of research and teaching and public advocacy. Universities are losing such potential scholars all the time.

We want to make sure that the university does recognize and value faculty members who are engaged with broader publics.

QS: Can you tell me a little bit about your own journey? How did you get involved with the public humanities? What motivated you to undertake and support publicly engaged work?

LA: Well, I was asked by the president of Hunter to step in to co-direct this program. Christa Acampora, who had been my colleague in the Philosophy department, had initiated the Mellon grant proposal, but then she left to take a job at Emory. So they needed somebody to fill the gap and I was asked to step in. But I am a true believer in this project.

I’ve done publicly engaged work in my own scholarship. My last book was on rape, the one before that was on whiteness, and so I have engaged with topics that have broad interest with larger publics. I come from an activist background and left college for three years to pursue some organizing. I always did activism alongside my scholarship and I found myself constantly thinking about why it is that this work is not valued intellectually.

There’s actually a lot of ridicule and snide comments made about intellectual stars like Carl Sagan, Martha Nussbaum, Edward Said, and so on. I think they’re dissed because it seems like they’re not really doing intellectual work in the public sphere. They’re taking the knowledge that’s been created in the Ivory Tower out to the hoi polloi—the masses—and that’s good work, but it’s not seen as intellectual work. There’s also this dissing based on the concern that some people want to be stars or to be rich, that their aims are not the pure, monastic quest for truth that are assumed to rule university ethical ideals.

I think the biggest mistake is to think that publicly engaged scholarship is not intellectual work or is lesser in some way. That’s the linchpin that we need to change for there to be a cultural shift within university life. This is more important that the question of motivations: the legitimate question is how is this work intellectual work. But we have many examples that show how it can be. Foucault, for example, engaged in prison activism for many years, and then he wrote Discipline and Punish—one of the most important books of political philosophy in the twentieth century. He could not have developed the analysis in that book without his public engagement. Now that book gets taught in prisons across the country and resonates with prisoners, but it is also an account that has helped to change our understanding of how modern power works in societies such as ours.

While it may not always be the case that publicly engaged work is intellectual work, with intellectual substance, it often is. And we need to see that as a possibility. We also need to see that engaging with larger publics informs, challenges, and expands our thinking. It expands our repertoire of concepts, our repertoire of problematics.

It depends on what you work on. But if you work, like me, on rape or whiteness, I feel it’s absolutely essential to engage with movements, activists, and all kinds of publics to make the philosophical analysis meaningful and informed.

While it may not always be the case that publicly engaged work is intellectual work, with intellectual substance, it often is. And we need to see that as a possibility.

QS: Absolutely! That’s such a helpful way to think about publicly engaged work. Can you also share a little bit about your involvement with the Mellon Public Humanities Program at Hunter? What are some of the projects students have pursued as part of this program?

LA: Yes, we have a program for public humanities scholars at Hunter College. I’m one of the co-directors, together with Professor Nico Israel, who’s appointed to the English programs at the Graduate Center and at Hunter. There’s also the invaluable Jonathan Fanton, who was the former head of the MacArthur Foundation and the former president of the New School.

The purpose of the program is to support undergraduate students at Hunter who want to undertake publicly engaged humanities projects, including both research work and organizing publicly engaged events. They pursue both components.

We invite applications to the program each year and we fund this work for the students. This year, we’re going to fund twenty-nine students. They get a stipend of $3,000 per year to help them, and this amount will go up next year to almost $4,000. They work with a faculty mentor and a graduate student mentor from the PublicsLab at the Graduate Center. We also provide programming for them through the year, and they work on topics of their choosing. I think letting them choose the topics they’ll work on is the best thing because they’ve expanded our imaginations in terms of what this work can look like.

For the most part, our students come from minority communities. They’re immigrants. They’re working-class New Yorkers. They’re from all kinds of backgrounds. And they’re connected to every conceivable community in New York. So, often, their projects are connected in some way to communities that they know intimately.

We recently had four students who did presentations on issues around minority representation. Two of them were Asian students looking at how the concept of the model minority is phenomenologically experienced by people designated as such, the harm that it has done, and the history of the model minority myth.

Another one of the East Asian students wants to be a journalist. So, she interviewed Asian American journalists in New York about what it’s like to cover China when you’re Chinese American. How do you establish your objectivity? Your credibility?

I have another student who has proposed to do a project next year on the census. Every ten years, the census changes its race and ethnicity categories. She wants to work on the gender categories and look at how the census may transform its binary assumptions and offer new ways for people to self-identify.

We’ve also had a student work on surrealism and Egyptian art, on African American music and the relationship between jazz and blues, and the experience of Indigenous immigrants from South America who are grouped under the Latinx category, which assumes they are Spanish-dominant, Catholic, etc.

There are just so many examples of good work that these students are doing! Some projects are political and some of them are aesthetic—for example, someone’s working on the effect of dance on mental health, while another person is working on the policing reforms that happened in Northern Ireland. Apparently, after the conflicts that happened in Northern Ireland, they really reformed their policing, and she wants to see what they learned that might be useful for reforming our policing practices in the United States.

QS: Since the program works primarily with undergraduates, I’m curious about whether you have any advice on how educators can encourage this kind of public engagement early on in students’ educational trajectories?

LA: Well, we try to sum up, at the end of every year, what we’ve learned and what we can do better. And this year we’ve learned one quite important thing. Usually, we tend to encourage sophomores to apply to the program. But that’s a mistake, we’ve come to realize. We really need to help students become aware of this kind of work from the time they’re freshmen. We need to make them aware that this kind of work is possible, and even desirable, in the humanities, and that they can do this work here at Hunter with our own faculty. It plants the idea in their minds as they’re taking courses and working with different faculty members.

I should say that the other point of the program is to show students that they can both go to graduate school in the humanities and do this kind of work. Sometimes they think that to go to graduate school in the humanities, they’re going to have to give up all their community and activist interests. We want to show them that that’s not the case, that more humanities graduate departments are doing this work, and that including this in their resume will actually give them a leg up. We want to provide all kinds of help to them, even on their graduate school applications, because Mellon is really concerned with diversifying the faculty in higher education in general (which we all should be doing).

At the same time, we also don’t want to say that everybody has to go on and get a PhD. We don’t want this program’s success to be judged in terms how many students end up in a PhD program and how many students end up as future faculty, because there are many, many ways to do humanities work at other organizations. For example, we brought in the head of the New York Public Library, the head of the New York Historical Society, the head of the Hispanic Society, the head of the Schomburg Center, a leading person at Amnesty International who does international human rights work, to speak to the students, to show them how people are using their humanities training in these varied ways. None of these are faculty jobs, but these are all people using their humanities training in an ongoing way at their diverse institutions.

QS: That makes a lot of sense. Does Hunter cultivate any institutional partnerships to facilitate this public humanities work?

LA: Well, we have a strong partnership with the Graduate Center—with the PublicsLab and with faculty there—because it can both augment what the Hunter faculty can provide and it also helps undergraduates establish connections with graduate students. It helps them imagine themselves as graduate students down the line, if they so desire. They often have a fear that graduate school is something so alien and different, something they could never do. This partnership helps change that perspective.

We know that there are other public humanities programs CUNY-wide, but we haven’t done enough to connect with them because we’re always scrambling for time.

Early on, Nico Israel and I researched the public humanities programs at Stanford, at the University of Michigan, and at Brown, in particular, to see how they did this work. We both knew people in those programs and we had planned to travel to those schools to speak with them. Then the pandemic happened. We still want to undertake that travel at some point. I don’t know whether it would end up creating a consortium, but it would certainly be valuable for us to talk to each other and explore what we can learn from them. These are very different institutions, though. I think the sad thing is that most of this work is dependent on soft money right now and, in places like CUNY with the budget cuts, it’s not clear that we can really institutionalize this work.

We’re also right in the middle of a three-week faculty conference, in which we’ve brought speakers from around the country to address the question of what is the “Democratic Commons.” The purpose of this is to showcase the importance of the humanities for the political crisis that we’re facing in the country today. The panel next Friday is going to be centered on media—social media, broadcast media, print media—which many of us view as a mechanism of publicly engaged scholarship. And yet, we often get doxxed, threatened, and attacked on these platforms. It’s going to be a panel of experts from around the country speaking to these issues.

The last panel, on Friday, April 23rd, is going to address monuments and commemorations. Both of these—commemorations and monument—as you know, raise all kinds of complicated issues. What is a monument? Should it be judged only aesthetically? What are people judging when they judge politically rather than aesthetically? How can one think aesthetically and politically at the same time? We have leading scholars whose experience and perspectives will help create a better understanding around what the stakes are in this debate. It’s not just a question of what should be taken down. How should that decision—of what should be taken down and what shouldn’t—be made? Who should make that decision? On what grounds? Should those monuments be destroyed or should they be kept safe and private space? There’s all kinds of interesting questions being asked.

QS: Last but not least, what are some of the biggest challenges you’ve faced while running the Mellon program and encouraging students to do this public-facing work?

LA: One of the big things is that students don’t get course credit for this work. They do a year-long research project with a faculty mentor and then they also have to have a public component—it could be a Wikipedia page, a podcast, a panel, a variety of things, but they have to have both elements, and our students are stressed and overworked. We haven’t been able to solve this problem of giving them credit. It has to do with how Mellon Foundation money works. It might be possible if we were no longer dependent on Mellon money. We might potentially be able to transform it in that way, because I think that in its current form, it’s just hard on students—this is an extra thing they have to do. Both we and they believe that this will enhance their work, their life, their own and their communities’ futures, so it’s worth doing, but it is an extra thing on their plate. We are endeavoring now to create an option for course credit for our students, thus reducing what else they have to do and making it more feasible for them to pursue these projects.