This spring, the pilot program of the Collaborative Research Seminar on Archives and Special Collections welcomed a cohort of twelve students to participate in two sessions—one at The Graduate Center Library, and the other in the Brooke Russell Astor Reading Room of the New York Public Library. We collectively discussed methods for engaging primary source materials in our research at the Graduate Center, CUNY, as well as encountered a variety of archival and rare materials—Timothy Leary’s papers, commonplace notebooks, an annotated SCUM Manifesto, books in parts, and many more. As a group, we grappled with a wide variety of questions, from citation management to experiencing enchantment and what it means to encounter primary source materials as embodied readers in space and time. A few of our participants volunteered to share their reflections on this process in the form of blog entries, which we are excited to share in the months ahead as documentation of the work we accomplished together, and as examples of the possibilities primary research affords.

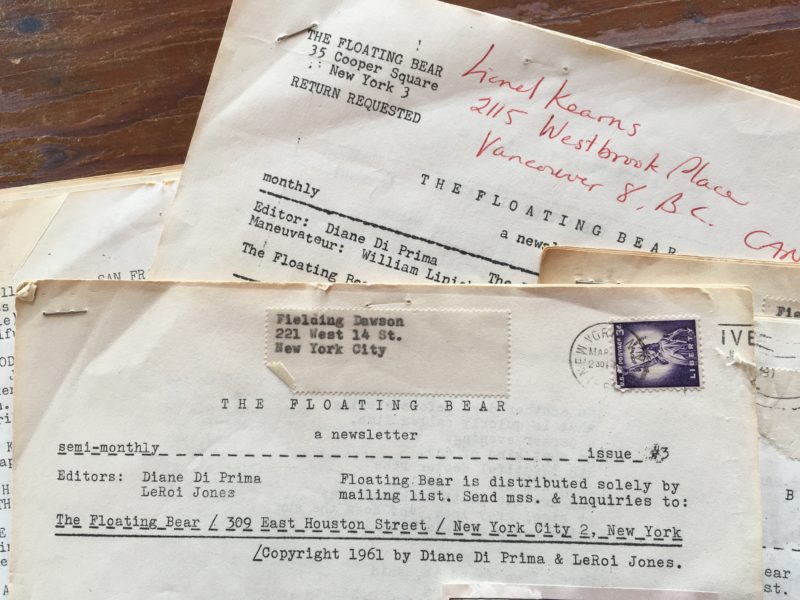

Below, you’ll find Iris Cushing’s account of her experience with postwar American literary periodicals, which led her to the Henry W. and Albert A. Berg Collection of English and American Literature during summer afternoons to work closely with The Floating Bear. She describes the relationship between physical material, social network, and the conceptual world of the poem in The Floating Bear, engaging the question of “free” and “freedom” as it relates to small press poetry publishing. This material network, as it were, radiates in spaces both within and beyond The New York Public Library; the images we’ve included of The Floating Bear are reproduced with permission from the Maud/Olson Library in Gloucester, Massachusetts, where I read copies of The Floating Bear at Charles Olson’s writing desk.

-Mary Catherine Kinniburgh, August 2017

A Labor of Freedom: Reading The Floating Bear at the Berg Collection

Iris Cushing

August 2017

I had the pleasure of participating in the Collaborative Research Seminar, a cross-institutional pilot program hosted by the Graduate Center’s Library and the New York Public Library, in the spring of this year. One Thursday evening in March, all of us seminar participants gathered after-hours in a reading room at the New York Public Library’s 42nd Street location to spend time exploring some of the library’s manuscripts and archives, and to discuss methods for conducting primary source research. The Graduate Center’s own Mary Catherine Kinniburgh (who is also a literary manuscripts specialist at the Henry W. and Albert A. Berg Collection of English and American Literature at the New York Public Library), along with Jessica Pigza and Thomas Lannon from Manuscripts, Archives, and Rare Books, set up numerous “stations” for viewing writers’ journals, correspondence, and a few archival literary periodicals. I work on New American poetry, and so I was instantly drawn to the issues of Semina that I saw out on the table. Semina was a very small-run literary-visual-assemblage-journal published out of California by Wallace Berman from 1955 to 1964. Encountering the marvel of Semina sparked my curiosity about what it would be like to encounter other independently published literary ephemera from this era in its original state. I was thrilled to hear that the Berg Collection has a complete set of The Floating Bear, a newsletter associated with Diane di Prima, who is one of my dissertation subjects. I had seen reprints and a digital edition of The Floating Bear, but I was now very curious to see the physical article. I set aside time over the summer to visit the Berg for this purpose.

The Floating Bear was a bi-monthly, mimeographed newsletter started in 1961 by Diane di Prima and LeRoi Jones (Amiri Baraka); the two edited, published and distributed it together until 1962, at which point Di Prima took over and continued the project on her own until 1971. Over two Tuesdays in July, I sat and read the first 14 issues, which span the first nine months of 1961.

The second issue of The Floating Bear, published in January that year, contains a critical essay by Robert Creeley titled “A Quick Graph,” where Creeley considers the notion of range in the work of his poet-peers (Charles Olson, Robert Duncan). He writes, “Range describes the world in the limits of perception. It is the ‘field’ in the old Pythagorean sense that ‘terms,’ as John Burnet says, are ‘boundary stones’ and the place they so describe the ‘field itself.’” Sitting at a green-felt-covered table at the Berg, reading this archival issue of the Bear, I felt a spark of recognition in Creeley’s metaphor of boundary stones describing a field. I find the metaphor to be an accurate one for the experience of reading The Floating Bear itself.

The “boundary stones” of the field that the Bear describes are the material conditions of the newsletter itself. Sliding the very first issue of the Bear out of its white envelope, I found myself holding a stapled packet of 8 ½ x 11” pages, creased long ago from being folded in half for mailing. There was a purple 3-cent stamp in the top right corner, and a typed mailing label above the masthead, bearing the address of the poet John Weiners. Instantly I envisioned the young poet on a day 56 years ago, checking his mail, loosening the staple holding the newsletter closed (a staple now rusty with age) and sitting down to read it.

The pages of the Bear consist solely of lines typed by hand. There are no graphics, columns, advertisements, or author photos. Di Prima typed the Bear’s contents—poems, essays, plays, critical texts and letters—herself on her IBM typewriter before making them into mimeograph sheets, which were then printed at the Phoenix Bookshop on Cornelia Street in the West Village. Baraka and Di Prima got help with proofreading from James Waring, and Freddie Herko helped out with managing the mailing list. They started out mailing the newsletter for free to about 150 poets, artists, playwrights and choreographers around the country; the list of recipients grew over the years to a few hundred. So, the ‘boundary stones’ include the canvas of the 8 ½ x 11” page, the typewriter, the mimeo, the mailing list. The field those stones describe is a magical field of inquiry, of affinity, of intellectual and spiritual freedom.

The tension between two simultaneous realities—between the boundary stones of the Bear and the wild, living, radical field of ideas and art it contains—is what interests me most about primary source research. To sit and be absorbed in reading an extra-literary artifact like the Bear is an experience of inhabiting two realities at once. Issue #2—the one that contains Creeley’s essay—begins with a beautiful poem by Frank O’Hara, “Now That I am in Madrid And Can Think.” The poem begins “I think of you/ and the continents brilliant and arid/ and the slender heart you are sharing my share of with the American air”. Reading the Bear, I feel that, like O’Hara, I am sharing breath with those who printed its pages. Those people are very close (their work is in my hands) and yet very far away (as it was made over half a century ago). In the Bear the names of the authors are placed after their work, so if I didn’t recognize the poem, I wouldn’t know who wrote it unless I turned a few pages. There’s no table of contents. The poem is the total focus of attention. I begin to read, my eyes wandering over the plain, uncluttered space of the page. The poem was typed on a typewriter, which gives it an intimate, handmade quality, as if it were written in a letter between friends.

And indeed, the Bear is a sort of letter between friends, many friends over long distances. Range. While Di Prima and Baraka were hanging out in O’Hara’s apartment, finding pages of poems wedged between couch cushions, Creeley was living in New Mexico with Bobbie Louise Hawkins. Duncan was in San Francisco, and Olson in Gloucester. Much of the dialogue among these poets happened in text—in the private space of correspondence, or in the semi-public of small-press publications. Like the numerous other “little magazines” central to the Beats, New American Poetry, the New York School, the Bear was a coming-together place, a way for poets and artists to engage each other asynchronously.

In her memoir Recollections of My Life As a Woman, Di Prima writes about the communicative space she and Jones were conscientiously building with the Bear. Di Prima recognized the importance of ongoing dialogue among the poets in her circle, and worked fastidiously to facilitate its happening. She writes,

“Not only the publishing but the networking too felt familiar. The linking of all of us through the magazine: Olson, Duncan, Dorn, myself, John Wieners. A kind of sixth sense of who was actually speaking to whom in a poem, a review, or article. Where it might be heading.

Years later, Charles Olson told me how important it was to him to know in those early days of the Bear, that he could send us a new piece of, say, The Maximus Poems, and within two weeks a hundred and fifty artists, many of them his friends, would read it. Would not only read it, but answer in their work—incorporate some innovation of line or syntax, and build on that. Like we were all in one big jam session, blowing. The changes happened that fast.”

Sitting and reading the Bear, I can see the changes happening, quickly—those stapled pages are a visible record of invisible shifts in values, aesthetics and knowledge. Issue #7 published Olson’s piece “Grammar,” a dynamic visual map of the evolution over time of the foundations of English grammar. In it, Olson describes the etymologies of words: “why,” “how,” “the,” “that,” “those,” “which,” “like,” and especially “a.” I can see that he is both recording his discoveries about these words, and actively figuring out for himself how parts of speech function.

In the following issue of the Bear, I see Olson’s investigation into syntax emerging in Joel Oppenheimer and Ed Dorn’s long poems. And I see Di Prima at her typewriter, caringly replicating these poets’ work, coming into intimate contact with the work. Receiving and transmitting its influence. There is an essay on the subject of “empire” by Robert Kelly in Issue #11, which concludes, “A deep breath then. Poets out in the open? The shadowy aimlessness of the poet’s motive the driving force of everything that moves? Which is close to the real burden of our responsibility.” In typing, mimeographing, and sending out this work, Di Prima took on a kind of responsibility for it, nurtured it.

I am a small-press publisher myself, and I find the sheer amount of labor that went into producing the Bear extraordinary. The 14 issues of the newsletter that I viewed came out every other week, which meant that Di Prima (as well as Baraka and their supporting friends) was working on it in some form every day. To read the original issues is to encounter that labor firsthand. The work is edited with the kind of precision that’s only possible through daily discipline. The Bear was always free—they “paid” Larry Wallrich at the Phoenix Bookshop in copies in exchange for using his mimeograph machine in those early days. At the end of Issue #2 is a statement: “We are in need of funds for paper and postage.” That end-of-issue request is reiterated in different ways in most issues: “we need dough or the Bear must go.” What strikes me about this straightforward ask is how it points to the very anti-capitalist nature of the Bear. No corporate entities sponsored it, nothing is advertised in it, and the publishers weren’t paid. Beyond being a “labor of love,” the Bear was a labor of freedom, a space for the free exchange of thought. This freedom occurred in multiple senses—anyone who wanted to could receive the newsletter, and read it with the knowledge that it represented only the minds and hands that had created it. Anyone could send in work for consideration. The essential element in the cultivation of this free space, however, was the “real burden” of ongoing work: attention to contemporary culture, yes, but also the nitty-gritty of finding money for stamps. There is something about holding the original artifact of The Floating Bear that expresses this freedom, and the responsibility that came with it, very powerfully. The world I encountered in these archives radiates outward into my present scholarship, contextualizing a larger ethos for New American Poetry: an ethos that holds the free life of the poem as its highest value.

-Iris Cushing